Why make offerings to Buddhas?

Mouse-size musings from the Dalai Lama's Cat

A balmy summer’s evening on the balcony of The Downward Dog School of Yoga. Class has ended, most students have gone home and now it’s just family – Ludo, the yoga school founder with his white, short-cropped hair, timeless face and eyes as blue as my own. Heidi, Ludo’s twenty-something niece, blonde and lissom. Sid, a modest maharajah who carries his wisdom with an effortlessly regal bearing, and his ever-graceful wife Serena. We have sat on this balcony together after class for many years, and there is a reassuring continuity about being here once again. Snug between Serena and Sid on an Indian carpet, I purr bountifully.

“There are few things as heartwarming as the sound of a cat purring,” observed Ludo after a while.

The others smiled as they sipped from after-class beakers of green tea.

“For me, it’s like an offering,” said Serena, who could be as extravagant as her mother, Mrs. Trinci, in attributing benevolent intentions to me.

“That’s a nice thought,” said Sid, reaching over to squeeze her hand.

This idea evidently set off a chain of thought for Heidi, because she looked preoccupied for a moment, as if deciding to ask something, before turning to Sid. “I’ve just gone on the shrine roster at Sukhavati Spa,” she told him.

He nodded.

What was currently the resplendent Sukhavati Spa had once been Sid’s family home. When he had redeveloped it and put into the hands of his friend Binita to manage, one of his few conditions was that the shrine was to be maintained.

A small room in the centre of the house on the ground floor, it was a simple, soft-lit space, the size of a small bedroom, furnished with a table on which sat a beautiful statue of Shakyamuni Buddha. In front of the Buddha were seven brass offering bowls. The shrine roster required a person to fill the bowls with fresh water each morning, and empty them at the end of the day.

Heidi had an uncertain expression as she asked Sid, “The thing is, I don’t really understand why we do this.”

“Make offerings to a brass statue?” he sought to penetrate her question.

“Oh, I know the statue is a symbol of real Buddhas,” she said. “And that the water in each bowl represents different offerings.”

“Food, flowers, lights, music,” interjected Serena. “The things we might arrange for an honoured guest.”

Heidi was nodding. “The thing is, why make offerings at all? I know there are some religions where people make sacrifices to the gods to stop them from being angry, or to gain their favour. Buddhism isn’t like that, it is? I’ve heard that an enlightened being, a Buddha, has no needs. They are beyond wanting anything.”

“A state of abiding bliss,” confirmed Ludo.

“So why do we need me to make offerings to them? Or is it just a tradition?”

“I understand,” Sid was nodding. “It’s a good question. Because you are right – Buddhas are beyond needs. They don’t want anything from us. And there’s no point carrying out meaningless rituals. So, when we make offerings,” he leaned across the balcony towards Heidi, “we do this for ourselves, much more than for the Buddhas.”

Heidi raised her eyebrows.

Sid regarded her calmly for a while before saying, “Buddhist teachings are all about transforming the mind, right?”

She nodded.

“External objects like statues and offering bowls are only symbols, external representations of our inner state.”

“Ja.”

“If we seek future happiness, especially transcendence, what is the cause?”

“Virtue,” she replied without hesitation, being well-grounded in the teachings offered by Geshe Wangpo every Tuesday night.

“Just so,” concurred Sid. “And one of the most effective ways to create virtue is by giving, including material things. If you are not well off, or a monk or nun, you don’t have money to buy stuff. So how do you give? By making offerings. In your mind – using water in bowls to represent what you visualise.”

“Imagining giving things,” said Heidi, beginning to understand.

“There are certain people and objects that, karmically speaking, are much more powerful than others. Among the most powerful are fully enlightened beings. There is more virtue to be gained in giving to a Buddha than to someone who is, for example, very unenlightened. So, if we can imagine the enlightened being who the statue represents, and we can also imagine our offerings as vividly as possible-”

“We create lots of virtue!”

“One other thing,” Sid held up his forefinger. “When we study karma, we learn that the more frequently we do something, and the more of a habit it becomes, then the more it affects our mind. So when we frequently make offerings to Buddhas, this becomes highly auspicious. We are creating the causes, especially, to see and revere enlightened beings in the future.”

“Wow!” Heidi murmured with surprise. “It’s a practice to cultivate our own virtuous mind?”

“Exactly,” said Sid.

For a while the group sat in peaceful contemplation of the conversation. Before Serena turned to look at Sid, “It’s a formal way to create great virtue. But I also like spontaneous offerings. They bring me joy.”

Heidi immediately wanted to know, “How do you mean, spontaneous?”

Serena looked at her, “Any time you feel joy. Contentment. Wellbeing. In your mind you can say, ‘I offer this happiness, this bliss to every Buddha and bodhisattva. May all beings feel the same!’ When I do this, I feel somehow lighter. And if I recollect that I, all beings, and even the Buddhas have no inherent existence, I feel even more uplifted.”

“A skilful way-” observed Ludo, drawing his hands together, “-to bring your mind closer to the mind of a Buddha.”

Heidi looked at Serena with warm appreciation.

“Any time of happiness that we’re able to recollect shunyata,” Sid was nodding approvingly, “becomes a moment of transcendence.”

In the pause that followed, my purring rose to full throttle.

“Like this moment?” inquired Heidi with a playful smile.

“Especially this moment!” declared Ludo.

The four of them chuckled and for a while all five of us were not only relaxing on a Dharamshala balcony, but also abiding in a more divine reality.

If you’d like to read my article about the four things that make an object karmically powerful you can do so here.

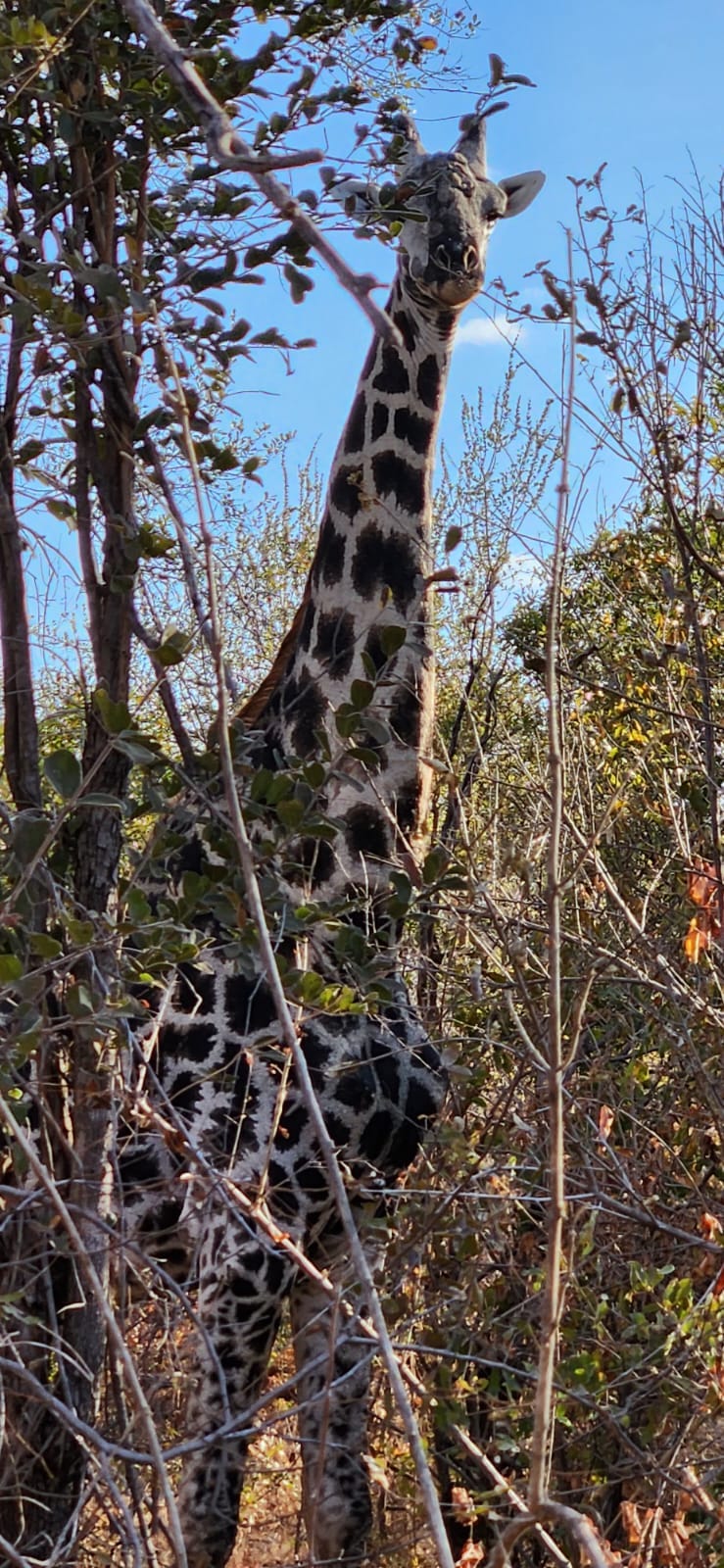

I am currently on Mindful Safari in Africa, where we are having an extraordinary time. I’ll share more with you in a future post, but for the moment here are a few pics from the past week during which we have had close and beautiful encounters with elephants, rhinos, buffalo, giraffe, eland, kudu, a glimpe of a leopard, and may other very special experiences, outer and inner.

Setting our motivation with a meditation under the trees at Masuwe Lodge.

On the road in our game vehicle … a quintessentially Zimbabwean winter bush scene.

We have been fortunate to enjoy frequent visits by a herd of elephant to the watering hole and mud bath directly in front of the Masuwe Lodge deck. Watching them is effortlessly mindful!

Mr. Giraffe browsing nearby. These majestic animals have the longest legs, necks, tails and eyelashes of any African animal.

The chefs and staff at Masuwe Lodge have been exceptional and every meal a delight. We do just about everything outside including dinners under the stars, sometimes joined by guest speakers when we sit around the fire-pit after our meal.

About half the money you help me raise through your subscription goes to the following four charities. Feel free to click on the underlined links to read more about them:

Wild is Life - home to endangered wildlife and the Zimbabwe Elephant Nursery; Twala Trust Animal Sanctuary - supporting indigenous animals as well as pets in extremely disadvantaged communities; Dongyu Gyatsal Ling Nunnery - supporting Buddhist nuns from the Himalaya regions; Gaden Relief - supporting Buddhist communities in Mongolia, Tibet, Nepal and India.

If you’re fairly new to my Substack page and would like to explore further, you can read my previous posts under the Archive button here.

Thank you for this mouse-sized musing, David. Sometimes the simplest act of giving gives the greatest joy and I will try to recollect shunyata too.

Thank you, also, for sharing your pictures from the Safari, they are wonderful to see.

Lovely post!