I am writing this week’s post from the Writer’s Hut where I usually stay when visiting Harare, Zimbabwe. By ‘coincidence’, I received a visitor myself while working on the story …

Of all the many superstitious beliefs about cats, there is one that contains just the teeniest grain of truth. This is the notion that cats seem to be attracted to humans who dislike them. If a cat strolls into a sitting room in which three unknown humans are seated, each of whom turn to gaze at this sublime manifestation of feline elegance, why will the cat unerringly head in the direction of the fourth and only person who has shown no interest in them at all?

Of course, you know that there is no great mystery to it, dear reader. Living your life in thrall to cats in general, and – if I may be so bold – this Himalayan in particular, you are fully aware that we cats don’t take kindly to being stared at. That averted eyes and calm restraint are, in our book, infinitely more appealing than overbearing stares and demands that we submit ourselves to being cat-handled. Of course, we will go straight towards the one person who shows no such intentions.

In fairness, cats are as illiterate in the ways of humans as the other way around. Which is why, thousands of years after moving in together, we often still fail to connect.

But there are some of us who are on the same page, not so? Some humans who are as perfectly fluent in cat, as their felines are in the ways of humans. In such cases, why would a cat ever approach a human who was clearly ignoring her?

Unless perhaps, through some subliminal tingle of the whiskers, the cat sensed that something was amiss?

Such was the case when I visited Chenrezig Sanatorium, the new facility across the road from Namgyal Monastery. A crumbling two storey structure until recently, it had only been the most unexpected bequest following the death of our dear friend and artist Christopher Ackland, that had seen the building restored to serene glory. Christopher had once expressed the wish for a place where broke old bohemians like himself could live out their days in delightful repose. Blake Ballantyne, the larger-than-life director of the new place, was creating exactly that. As the months went by, a trickle of elderly individuals found their way to McLeod Ganj, and the hilltop home with its spectacular views.

Chenrezig Sanatorium was not the kind of place I’d usually visit. Being a cat wobbly on her pins, the steep drive up to the building would have been prohibitive. But among Blake’s new staff were two monks formerly known as novices Tashi and Sashi. They were under strict instructions to ensure that, should I ever come into view of the gate camera at the bottom of the hill, I was to be collected immediately. It was a duty they were most willing to fulfil, always accompanied, I noted, by much whispering of mantras.

On a visit to the Sanatorium in early autumn, I walked through an arched French doorway into an expansive salon when I came across four people playing bridge – two men and two women. The atmosphere around the table was most convivial, and as I appeared, the two women immediately were immediately calling out, “Isn’t she beautiful!”

“That gorgeous coat!”

“How unusual to see a cat around here. No one has brought a cat with them, have they?”

“Look at those blue eyes!”

Residents were encouraged to bring their pets when they moved in. So far, a motley assortment of poodles, golden retrievers and a spaniel had arrived, all of them affable and, I noted with satisfaction, unwilling to risk the wrath of a Snow Lion.

One of the men glanced at me only once before looking away. Silver haired and nattily attired in a royal blue roller neck and cream jacket, he returned his attention to his cards, while the three others tried all they could to coax my attention.

“You had a cat, didn’t you Nate?” one of the women inquired of him.

“Mm,” he pursed his lips, deeply immersed in his hand of cards.

Naturally, I was intrigued to come across someone impervious to my charms. Can you imagine, dear reader? Quite extraordinary!

Nevertheless, I am a cat who knows how to play my cards too, so I padded out of the room to the courtyard beyond, leaving them to their game.

On a subsequent visit, two men were sitting on one of the long day beds set against the veranda wall, one that offered views not only of the garden, but the panoramic Himalayas beyond. Deeply engaged in concentration, they didn’t see me approach until I launched myself onto the bed between them.

I had no idea who they were until I landed.

“Good Lord!” exclaimed one of them. “Where did this one come from?” he reached out to stroke my neck.

The other man turned out to be the bridge-playing Nate. Today he was wearing an emerald-green roller neck. He looked at me with an intense expression I found impossible to fathom, before abruptly turning away.

“You don’t like cuddling cats?” the other man was stroking my back with generous sweeps.

“I daren’t,” replied Nate, before patting his trouser pocked. “Must get my phone.”

With that, he got up and walked away.

Daren’t, I mused. And that look of his. Not exactly the signals of someone who was allergic to cats. So, what was going on with him?

A couple of weeks went by before my next visit – an afternoon during which things had proved to be too noisy for my liking at the Himalayan Book Café and altogether too quiet at Namgyal Monastery, His Holiness being away. Somehow, I found my way to the gates of Chenrezig Sanatorium and, moments later, I was being ferried up the hill among a shower of Heart Sutra mantras.

On that late autumn afternoon, I felt suddenly tired. There was no end of hidden nooks and hidey holes where a cat could rest peacefully. I was drawn to a tub of exotic looking orchids near the door of one of the ground floor apartments. A vivid blue and yellow, I was taking in the unusual shapes and colours of the blooms, and the strange tangle of roots from which they emerged, when I noticed that the doors of the apartment were open. Only a gauze curtain was drawn across the entrance – one that was easily pushed aside.

The apartments in this building were all variations on a theme. A large living room led to smaller kitchen and dining area. Adjacent to these was a bedroom with ensuite bathroom. The sitting room of this apartment was empty, and apart from minimalist if comfortable furniture I was able to see little of detail in the dim light. But observing a large, framed photograph of a tabby on a wall shelf, I knew that I was in the home of that most particular of human beings: a cat lover. I was confident to venture further.

I made my silent way into the bedroom. Someone was having a siesta on the bed. I leaped up to find that it was none other than Nate. Wearing, today, a carmine red roller neck. He was lying on his side, sleeping, and I decided that his bed was exactly the place I myself might doze undisturbed. After a cursory grooming, I lay down facing his direction.

Next thing I was aware of, his hand caressing my neck.

“Did he send you?” he was asking.

Woozily coming to, I recollected where I was and how I’d got here.

“Are you here because of my boy Merlin?”

I wasn’t, as it happened, but as I stretched my front paws out tremulously, as one does on wakening, I pressed my left paw firmly into his nose.

“I wondered.” He evidently took my movement as an assent.

“Well, you tell him that I’ve never stopped thinking of him,” he was stroking me firmly now. “First thing when I wake up every morning. Each night when I go to bed and he’s not here,” Nate’s eyes welled up. “I miss him so much!”

It was then I realised what that intense expression had meant, the afternoon on the day bed. Why he said that he ‘daren’t’ touch me and hadn’t been able to bring himself to even look at me in the salon. He was heart-broken. Desolate. He didn’t want to be reminded of the love he so deeply missed.

After a while I left him on his bed and headed back through the main entrance of the building to the administrative offices. There was one place I knew that I would be left to doze undisturbed. Finding the door of the Director’s office ajar, I walked to the banquette of a bay window overlooking the garden, and hopped onto it, the stone casket from Gandhara mounted nearby, a reassuring object on which to allow my gaze to soften, before the welcoming embrace of sleep.

There I lay for quite some time, occasionally hearing Blake Ballantyne’s rumbling voice as he attended to business. I knew that Blake would no sooner disturb me than I would force him awake if I was ever to discover him napping. He was, after all, fluent in cat.

What roused me to consciousness was not his rich, baritone, to which I was accustomed, but the lighter voice of a visitor. One, it seemed, who had come to see Blake not in his capacity as director, but as counsellor.

“I’m still quite new to things,” the visitor was saying. “And to the … ideas you have here. But am I mistaken, or do Buddhists believe that sometimes quite … magical things can happen?”

Blake’s chuckle reverberated about the room. Remaining on my side, I opened my eyes to catch a glimpse of carmine red from a wingback chair, angled with its back to me.

“I think you’ll find that all the great traditions report such things. Even,” he said mischievously, “some of the not-so-great ones! But what kind of magical thing do you mean?”

“This may sound crazy,” said Nate. “But today I had the feeling that Merlin, my cat who died seven years ago, caused a … visitation.”

Blake listened attentively.

“I don’t know whether it happened for real, or was just a dream. I was having a lie down.”

“Uh-huh.”

“In a way it doesn’t much matter. I mean, whether the cat manifestation was real or whether I just dreamed it.”

Blake was facing Nate – and therefore me, in the spot I occupied when visiting his office.

“I have seen a stray cat around here a couple of times.”

“Stray cat?” probed Blake, looking directly at me.

“None of us residents have cats, do we?”

“No, no” confirmed the Director.

“What interests me,” there was an urgency to Nate’s tone, “is, from a Buddhist point of view, what it means?”

I could well imagine the intensity in his eyes as he asked the question. And having surfaced from my languor, I was as eager to hear Blake’s answer as he!

“From a Buddhist point of view,” Blake carefully framed his response, “The starting point is that anything in possible and nothing can be ruled out.”

“I see.”

“The more interesting question is: why? Whatever it was that happened, what might have been the reason for it?”

“You mean, for Merlin sending me this cat?”

“Yes.”

“That’s why I’m here. I have no idea! I miss my little boy so much,” Nate choked on his words. “For seven years! I think of him every day. People have said I should ‘replace’ him. But you can’t replace a living being. He was so very special! You can’t turn your back on someone you love.”

Blake got up to collect a box of tissues from his desk. Nate helped himself to several.

“What this seems to be about,” Blake said, giving Nate a chance to compose himself, “is grief. The loss of love.”

“Yes,” sniffed Nate.

“Seven years is a long time.”

It was a while before Nate responded, “I know.”

“Do you have any thoughts about where Merlin may have moved on to?”

Nate shook his head. “He was such a great companion, it must be somewhere good. But you tell me,” he said to Blake. “What do Buddhists say about such things?”

“Pretty much as you outline. Causes created in one life are experienced in the next. So, a very favourable reality for the being once known as Merlin. Which is the interesting thing about grief.”

“Why interesting?” Nate was hesitant.

“Interesting because after a while it is rarely about the being we grieve. The one who has moved on. It’s about the one left behind.”

“The love we have for the one who died?” queried Nate.

“Love is the wish for other beings to be happy. I have no doubt you wish for Merlin to be happy. From what you say, there’s every likelihood that he is. Attachment, on the other hand, is about our own feelings. The pain we experience when we lose a loved one. Which seems to be about them but it’s actually about us.”

“But it’s normal to feel attached!” Nate protested.

“’course it is! You wouldn’t be human if you didn’t have emotions. If you didn’t feel pain. But when we keep carrying that pain for month after month, year after year, that’s when pain becomes suffering. And if we’re not careful, we get into the habit of it. It becomes ingrained in our sense of who we are. We feel,” he gestured towards Nate, “disloyal about moving on with our own lives, even though that is the healed, positive way to move on given life’s only great certainty.”

“Which is?”

“That our own life is fleeting, ephemeral. Before we know it, we too are going to die. Life is too short to spend years of it grieving. Suffering over the loss of someone who has long-since embarked on their own, fresh adventures. Easy for me as I sit here, I know.”

“What you said about being into the habit of it,” Nate sounded rueful. “I can see that.”

“Mm,” Blake allowed his visitor time to digest what he said. Before adding, “With pets in particular, there is another dimension to be considered also.”

“Oh?”

“Most rescue centres I know are at capacity with dogs and cats needing homes. Animals used to being a much-loved family pet who, for no fault of their own, find themselves in a form of prison. All they yearn for is freedom. A walk in the park. Someone to love them and to show love towards. How does it sound to say, ‘I’m going to leave you behind bars because I can’t bear the pain of losing another pet’?”

Nate listened to this in silence before saying, after the longest of pauses, “Food for thought.”

From outside came the sound of a bell being rung in the sitting room announcing four o’clock tea.

“Perhaps it is a message you have been offered today,” suggested Blake as his visitor rose from his chair soon afterwards.

“Maybe,” agreed Nate. “Not the kind of message I thought. A different one.”

Winter brought an end to my daily adventures. During the succession of long nights and short days, of winter storms and snow, I remain huddled in my quarters with the Dalai Lama, with only brief forays, during sunny interludes, to the Himalayan Book Café.

During this time, reminded of one of the Dalai Lama’s most frequently quoted sayings, about how pain is inevitable but suffering is optional, my thoughts turned to Nate in his room at Chenrezig Institute. Was he still mourning his beloved Merlin, I wondered? Was he still carrying the pain.

I heard Oliver, His Holiness’s translator, quote the fable of the two monks reaching the bank of a fast-moving river who encountered a frail, elderly woman who wanted to cross, but feared she’d be swept away. Setting aside his monastic vow never to touch a woman, one of the monks hitched the old lady onto his back and thus carried her to the other side.

The monks continued on their way. At nightfall the companion of the good Samaritan told him, “You know, according to the rules, you really shouldn’t have carried that woman across the river,” he said. To which his colleague replied, “I set her down five hours ago.”

Was Nate finding a way to set Merlin down? Or was he still burdened? ‘Acknowledge, accept and let go’ was easy enough to understand, but difficult to practice when we are in the habit of clinging to lost love, holding it so tight to our heart that it causes us anguish.

Spring came, and with it, new life. Finding myself in the garden next to the monastery one morning, the one which directly overlooked the gates to Chenrezig Institute, who should I see venturing from the pedestrian gate next to the main entrance but Nate. Holding a lead. At the other end of which was a somewhat moth-eaten looking Pomeranian.

“This way, Benjie!” he called breezily, directing his pooch in an out-of-town direction.

I felt the sun warm up my coat. It seemed that Blake Ballantyne’s wise counsel had prevailed, and that Nate had found a way sufficiently to let go, allowing for new possibilities.

I couldn’t help being curious about what would happen next time I found myself across the road as a visitor. Having resolved his past hurt, would Nate join his fellow residents in competing for my attention if I entered a room. Would he try to coax or wheedle me onto his lap? It seemed distinctly possible, dear reader. In which case I would, of course, completely ignore him.

Stray cat, indeed!

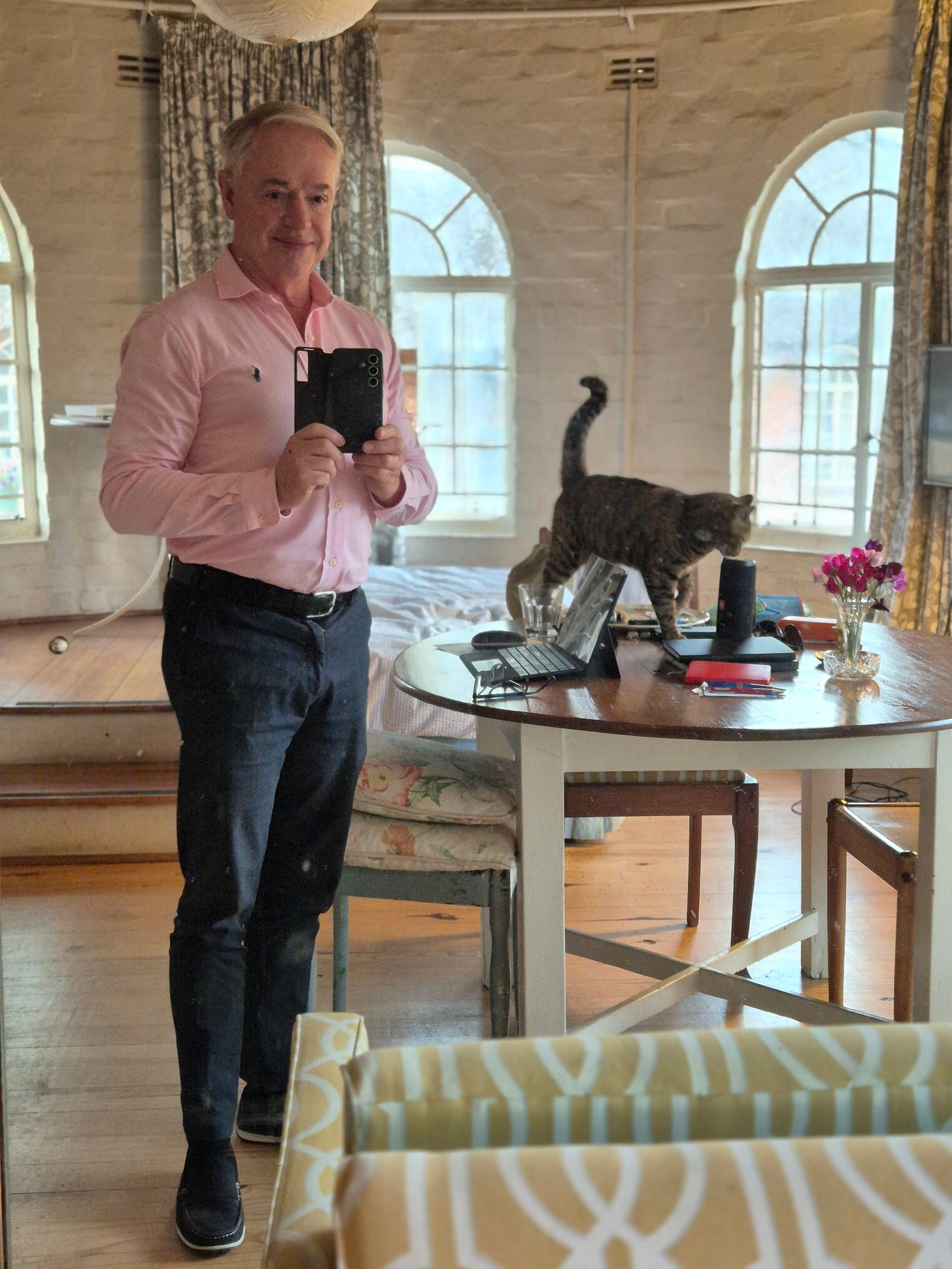

When I received my own visitor, I studiously ignored her while she hopped on the table to inspect the tools of my trade …

… okay. You’ll do!

What a very touching story, David; thank you. And lovely to see the photos of you with the cat also. 🥰

Four weeks ago today, we cremated our beloved Leela dog, who filled our lives with great joy and sweetness. A rescue dog with a very traumatic history, she transformed from a depressed, subdued, anorexic creature into a big, bold and exuberant personality full of life, love and playfulness right unto her last moments despite being in pain.

We are full of gratitude and heartbreak; and just as you say, it's been a profound reminder of impermanence and the need to chant and meditate for her, for ourselves, and for the benefit of all beings.

Thank you once again, David, for your continued writing, comforting, teaching and awakening activities. 🙏🏼💖

Dearest David 🙏 What a great story to remind us of the suffering caused by attachment. With any kind of attachment, suffering will follow.

May all beings find happiness ....... Thank you🙏