Read the prologue and first chapter of The Dalai Lama's Cat and the Four Paws of Spiritual Success!

Prologue

Are you curious, dear reader? If you were to find yourself padding past an alcove concealed by a curtain, would your every instinct be to tug back the fabric—or, indeed, push under it—to see what lay behind?

Making your way down a familiar street, if you came to a door which, for your entire existence, had been closed, but today was ajar, would you pause to take a good, long peek inside? Or at the very least, steal a sideways glance? And if that door led to a mysterious corridor which, in turn, opened onto a secret courtyard, or perhaps a lamplit room filled with intriguing artefacts, might you be tempted to venture inside?

Oh, there’s no need to reply. I already know your answer. That’s something we have in common, you and I. You are not the kind of reader—and I am most certainly not the kind of cat—satisfied by mundane routine. We have inquiring minds, do we not? We ask questions. Discover things. Leave a newly emptied cardboard box in the middle of a room, and we will be the first to jump inside it.

And I’m not merely being literal. As you will also have assumed. Which is another thing we have in common, you and I—the wish to have fun while exploring possibilities of the greatest profundity. Why communicate on a single level, pray tell, when you can do so on two levels simultaneously? Where’s the joy in that?

Of all the subjects about which we’re curious, the one that makes our tails tingle and whiskers positively quiver is, of course, the one that concerns our ultimate purpose, our deepest wellbeing. What are our destinies, dear reader, and how may we affect them in this lifetime and whatever follows? Is it true that the nature of our mind is radiant, boundless and serene? If so, how do we go about experiencing this extraordinary reality?

There are different places a cat might seek out answers to such questions. One such venue, a place teeming with great wisdom, is The Himalaya Book Café, one of my favorite places in the world. A short distance down the road from Namgyal Monastery, where I live with His Holiness, the bookshelves of this delightful emporium offer a treasure trove of spiritual and esoteric reading. Among the many titles, you will discover global bestsellers along the lines of: The Six Laws of This, The Seven Habits of That or The Eight Rules of The Other.

Just looking at them puts me in the mood for a nap. How much effort would it take to plough through all those earnest volumes, I sometimes wonder? To try to remember all that they contain? Then to apply the laws, habits and rules to one’s own life? Do people actually go through life constantly monitoring their activities against a checklist of items which grows in length every time a new such book is propelled onto the bookshelves?

It all seems very complicated. Unnecessarily so. Because day after day as I sit on the windowsill, listening to His Holiness offer wisdom to countless visitors, he is never complicated. Guests don’t leave his office clutching life prescriptions itemizing six of these plus seven of those, like a bubble pack of multi-colored capsules to be ingested daily. On the contrary, the Dalai Lama’s advice is usually very simple. And as a famous cat once said—it may even have been me—simplicity is the ultimate sophistication, is it not?

Rather than venturing down to The Himalaya Book Café and the latest batch of imports, if it’s enlightenment one is after, then it’s far better to stay at home. Sprawled in the dappled light of my delightful, first-floor sill, where I can keep an eye on the courtyard below and all the comings and goings at Namgyal Monastery. The perfect vantage point from which to maintain maximum surveillance with minimum effort.

For years I have sat in this same spot following the change of seasons outside, while eavesdropping on His Holiness’ conversations within. For years I have been on the receiving end of compliments about the adorableness of my sapphire-blue eyes, my charcoal-colored face, the sumptuousness of my cream coat, and the delightful bushiness of my grey tail.

When the Dalai Lama rescued me from almost certain death, and I was a mere scrap of a kitten, everything in His Holiness’ apartment was fresh and exciting. In those very early days I was confined to the first floor, a space quite big enough for a tiny, if inquisitive, being. Seven years have passed, and I have long since become thoroughly acquainted not only with His Holiness’ apartment, but also with every nook and cranny of Namgyal Monastery, not to mention all the most interesting neighborhood haunts. They are all now familiar territory.

Recently I came to realize that, without setting out to do so, I have become equally familiar with the conversations that go on within. During my earlier days, intrigued by every passing prince, president or pop star, the questions they came with were as new and unfamiliar to me as the Dalai Lama’s apartment had been, when I was a tiny kitten.

Seven years on, I have come to realize that whatever questions they may ask His Holiness, the answers are always variations on the same themes.

However, instead of becoming bored with these teachings, the opposite is true: the more acquainted I become with them, the more deeply they touch me. Whenever I hear the Dalai Lama explain the value of loving kindness, in his distinctive bass voice, I find myself resonating with exactly those same qualities, as though by transmitting the idea, he makes them manifest. Whenever he throws back his head and laughs—which he does often—he simultaneously releases a joy within me, and whoever else is in the room, that is quite palpable. And whenever he explains the path to fulfilment and inner peace, I am struck with such a profound sense of wellbeing that I wish it could ripple out to every being possessing fur, feathers or fins—as well as those relative few on our planet who do not—so that we may all come to know our own true nature as a tangible, all-pervading truth.

And I have also come to understand another thing: the reason why so many people seek out the Dalai Lama isn’t necessarily because of what he might say. It’s because of the way he makes them feel. Words and insights may be important, because they suggest the reason for the way he is why he is. They point to how we, too, can cultivate those same qualities we find so attractive in him. Long after people have forgotten every last word that His Holiness has said, they still remember how he touched their heart. And they love him for it.

Often at the end of an audience with His Holiness, a visitor will ask if there’s a book they should read to understand the Tibetan Buddhist path. The Dalai Lama may give them a copy of a recommended title—such as Shantideva’s classic, Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life. Alternatively, he may recommend another book, or ask one of his Executive Assistants to provide more details to the visitor on the way out.

Whether or not his guests ever get around to actually reading these books is an interesting point. For it seems as if, in asking for a book suggestion, they are requesting a keepsake. A souvenir. Something to keep alive the extraordinary flame lit by his presence.

One evening around five o’clock, His Holiness’ two Executive Assistants came into his office for their daily review. As always, Oliver, the Englishman who worked as the Dalai Lama’s translator, had poured three cups of green tea which they were enjoying. Tenzin, His Holiness’ adviser on monastic matters and the quintessential diplomat, sat next to Oliver on the sofa facing their boss. I was sprawled out on my own armchair next to His Holiness.

‘We gave your American visitor the book you requested,’ reported Tenzin. A famous talk show host had visited us earlier that afternoon.

The Dalai Lama looked pensive for a few moments, before shrugging. ‘A useful book. Perhaps he will read it. But for him, maybe, not ideal.’

On the sofa, Oliver and Tenzin exchanged a significant glance. The matter of what book to offer visitors was one they had discussed many times over the years.

Oliver, being a Westerner, was often more forthright than the others in the Dalai Lama’s circle. He leaned forward on the sofa, ‘Your Holiness, what would an ideal book look like?’

The Dalai Lama nodded as he pondered, before saying, ‘It must cover the key elements of the path.’ He used both hands to sweep a circle in front of him. He listed the themes with which I had become long familiar. I counted them. There were four.

‘An introductory book?’ queried Oliver.

His Holiness held up his right hand in a cautioning way. ‘But not simplistic.’ His eyes met Oliver’s with a mischievous twinkle. ‘You Westerners are not quite the barbarians that we Tibetans thought you were back in the 1960s.’

They all chuckled. When lamas first emerged from behind the Himalayas to go to Europe, USA and Australia, they had imagined that Westerners, steeped in their materialist ways, would have little interest in the subtleties of mind training, let alone exploring the true nature of their own consciousness. What they’d found had astonished them.

‘High level, but not dumbed down?’ queried Oliver.

‘And …’ His Holiness continued, ‘the book should include explanations about the mystical things,’ he chuckled again.

‘You mean like oracles?’ asked Oliver with a grin. ‘Telepathy?’

I turned my head to tune in more closely.

The Dalai Lama nodded as he laughed.

‘Astral travelling and the like?’ continued Oliver.

I noticed that Tenzin was taking no part in the conversation. Still seated beside his fellow Executive Assistant, it was as though he had dissolved into the background, removed himself from the conversation by his reticence.

At this point His Holiness looked directly at Oliver and said, ‘As my translator on so many books already, perhaps you would like to write this one?’

In an instant I realized why Tenzin had been keeping so quiet.

Oliver began coughing, his pale face turning pink. ‘Your Holiness!’ he spluttered.

‘You are familiar with the main themes.’

‘Yes, but …’ Oliver was gripped by another paroxysm of wheezing. For this man—a translator, no less—who usually had no difficulty giving voice to the most nuanced and complex matters, to be rendered speechless was most unusual.

As he was doubled up, gasping for air, the Dalai Lama glanced over at Tenzin with a playful twinkle. ‘You could think of a title that is …’ he tried to think of the word.

‘Catchy?’ prompted Tenzin.

‘Yes. Like in the airport bookshops.’

Given his constant travels, these were places with which His Holiness was familiar. Glancing over at me, the Dalai Lama seemed to be reading my mind—and not for the first time. ‘The Six Rules of something!’ he gripped the arm of his chair as he chortled.

Recovering from his coughing episode, Oliver realized he was being made fun of. Sort of. Though perhaps not entirely. He gave careful thought to what he was about to say. ‘The ideal book should explain the main themes of Tibetan Buddhism. And what people find magical—like rebirth and so forth. But that isn’t enough.’

The Dalai Lama raised his eyebrows.

‘What people want, more than anything, isn’t just your wisdom. It’s the way you make them feel. We need to somehow communicate your presence.’

In an instant I realized where clever Oliver was going with this. ‘I’m not sure I’m the right person to do that,’ he said.

His Holiness pondered for a moment before asking. ‘Then who is?’

Deciding we must be getting near dinnertime, I stirred on the armchair, stretching out all of my legs with a luxuriant quiver.

The timing of this maneuver, I have to confess, was as crass as Oliver’s point had been subtle. Around the table, all three men laughed. ‘I think we have a volunteer,’ chuckled the Dalai Lama.

‘And perhaps a catchy title?’ suggested Oliver, gesturing towards my outstretched limbs. ‘The Four Paws of Spiritual Success!’

They all chuckled before His Holiness observed, ‘That’s not such a bad title. After all, the Tibetan Buddhist path may be said to comprise four particular aspects. Four practices which are our challenge to embody.’ Gesturing towards a beautiful image of Shakyamuni Buddha hanging on his wall he murmured, ‘We are reminded of these four elements every time we see the representation of an enlightened being.’ Oliver and Tenzin nodded sagely.

I looked over at the wall-hanging. Reminded of four elements, I wondered? Were we?

Later that evening, I was perched on the bed, paws neatly tucked under me, while the Dalai Lama sat close by, meditating. This was one of my favorite times of the day, our room lit with the soft glow of a solitary lamp. His Holiness’ powerful, yet gentle compassion pervaded outwards beyond this room, and even Namgyal Monastery, to encompass lands and realms of existence far beyond. As the focus of his meditation turned to loving kindness, I began to purr softly, continuing all the while until he finished his session.

That was when he reached out to stroke me. ‘They are right, my little Snow Lion,’ he said, using the very special name which only he ever called me. In Tibet, snow lions are a symbol of fearlessness, power and joy. ‘You are tuned in.’

I purred even more loudly.

‘You have listened to me for thousands of hours,’ he continued to massage my face with his fingernails, just the way I liked it. ‘You know the wisdom to be shared. Most of all,’ he leaned over, briefly whispering in my ear, ‘you know how to communicate loving kindness.’

As my purr rose to a crescendo, I turned to meet his eyes directly—a privilege bestowed only rarely by we cats.

‘If you can help make others feel this way,’ he touched his heart. ‘Wonderful!’

Which is how, dear reader, you come to be holding this book in your hands. As much from a wish to convey an energetic presence, a feeling, as the profound wisdom of the Dalai Lama.

But if I may let you into a secret at this early stage, the sense of oceanic wellbeing people so frequently feel in His Holiness’ presence isn’t actually coming from him. He is an enabler, if you will, a facilitator. He is so pure of heart and so utterly free from ego, that what he does is reflect back to those he is with their own, ultimate nature. Their highest version of themselves.

If you’re wondering how the presence of an enlightened being, a bodhisattva, may be communicated on the pages of a book written by a flawed and complex—if extremely beautiful—cat, let me confess that my only job here is to offer you a mirror. A looking glass of a particular kind. One that reflects back not the contours of your nose or the arch of your brow, but which provides a much deeper reflection of who and what you are. One which penetrates beneath the surface persona with whom you are no doubt all too familiar, to the truth of the consciousness abiding within.

This is a reflection with which you may be unfamiliar. One which may even catch you unawares. Look closely—there’s no need to be afraid. What you will discover, if you ever doubted it, is that your own true nature is quite different from whatever blemishes and imperfections may temporarily obscure it. Self-criticism may drive you to focus on your own failings so much that you appear profoundly tainted; but the simple truth is that whatever abides in your mind is only ever temporary. Fleeting. Your consciousness can never be permanently contaminated, no more than water can be.

As we will explore in the pages that follow, the delightful truth is that the enduring qualities of your mind may be quite different from what you might suppose. Your consciousness is, in reality, both boundless and radiant, allowing any thought or sensation to arise, abide and pass. Once you penetrate beneath whatever surface turmoil may sometimes exist, your mind has the quality of tranquility that is, in fact, oceanic.

And if these statements seem as extravagant as my own sumptuous fur coat, let me add just one final observation, dear reader. At heart, you are a being whose pristine nature is nothing other than pure, great love and pure, great compassion. Mine too!

Chapter One

I could hardly believe my own eyes! Sitting beneath Mr Patel’s market stall at the gates to Namgyal Monastery, the same place I had once observed him from my first-floor windowsill, was the most magnificent, mackerel-striped tabby in Dharamshala.

Could it really be him? Mambo, the father of my kittens? The gorgeous, muscular beast who had appeared in my life when I was still an impressionable young feline-about-town—before, just as enigmatically, vanishing?

My paw steps quickened, which required no small effort. The street outside The Himalaya Book Café, where I had spent the afternoon, had quite a slope to it. I was no longer in the prime of youth. And my rear legs hurt more than ever.

From the time I was tiny when I had been dropped onto the pavement, I had suffered from wonky back legs. Legs which had always felt awkward, and lately had even begun to burn.

Pushing through the pain, I made my way towards the gates as quickly as I could. With monks coming and going through the entrance, and market stalls plying their trade directly outside, a cat could easily slip out of sight in the general tumult. Especially one as well camouflaged as a tabby.

I hurried ever faster, ducking behind the row of stalls. I headed towards Mr. Patel’s stall, the last in the row. Scanning through the moving legs and robes and saris, I tried to keep track of the unexpected visitor.

But he was no longer there. Nor on the nearby tree trunk, where he used to climb. I paused, surveying the area, wondering where to go next.

Suddenly, from behind a garbage bin, just a few feet to my right, I heard a low-pitched yowl. It was filled with menace. Instantly, my fur stood on end. Spinning round, almost losing balance, I was confronted by a ferocious tabby. Most definitely not Mambo. Savage of face and fur bristling, he was pure aggression.

I bared my fangs. He unleashed another, even louder, bloodcurdling warning before leaping forward. He was now only inches away. Well within striking range.

Instinct took over. I raised my right paw and snarled back. People were turning from Mr Patel’s stall, voices raised in alarm.

The interloper, demanding dominance, fixed me with a gaze of total hatred. Young and lithe, no doubt he believed he could beat me in any fight.

But I wasn’t giving way. I had been pursued in the past. I’d learnt not to run at the first sign of threat. My resistance only seemed to provoke him further. Incandescent with rage, he lashed at my head, huge claws extended.

People were screaming. And next thing there was a crash! A feeling of cold wetness. Human legs pushing between me and the tabby. Someone had thrown a pot of water at us. In the moments afterwards, I was scooped up and taken inside the gates of Namgyal before being set down in the courtyard. I glanced round, to see the tabby being shoved forcefully away.

There are some advantages to being recognized as the Dalai Lama’s Cat.

With as much dignity as I could muster, given my soaking coat and shaken state, I returned across the courtyard to our building. The pain in all four paws was now so acute that it felt like I was walking on hot coals.

I skirted the building to the ground-floor window that was left open as my private entrance. Once inside, I stopped to groom myself. The water that had been thrown at us had been used to boil somebody’s lunchtime rice. It was sticky and starchy, and tasted disgusting. Lifting a paw to my face, I felt a rawness where the intruder had clawed me—thankfully, my thick coat had protected me from worse damage.

Some minutes later, I made my way upstairs to the apartment I shared with His Holiness. On a normal day, it was bursting with warmth and kindness. But today the rooms were silent and in semi-darkness. The Dalai Lama was away travelling. It would be some days before he returned home.

I sat on the sill that evening, watching twilight fall over the Namgyal courtyard, looking across at the green light that burned at the end of Mr. Patel’s market stall, and I felt very, very sorry for myself indeed.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

His Holiness arrived home several days later, and life instantly resumed its usual brisk pace. Arriving home late morning, the Dalai Lama barely had time to greet me before Oliver was in his office, ready to brief him on the guests who’d be arriving for lunch in less than an hour.

The subject of that day’s gathering was ‘Dharma in the Digital Age’, a topic of some fascination if you didn’t have more pressing things to worry about. Which I most certainly did.

For starters, that most unpleasant ambush by the tabby cat still had me badly rattled—I had never been threatened by another cat before. Namgyal Monastery had been largely feline-free, and therefore my private domain, for as long as I’d lived here. Having another cat show up and act like it was his territory was a most unwelcome development.

Of more immediate concern were the stabbing pains I felt whenever I walked. They had started, ominously, the day of the tabby ambush. And as each day passed, they seemed to get worse. Visits to The Himalaya Book Café had become so excruciating that I’d even begun to question whether a visit for my favorite sole meunière could be justified, given the torment inflicted every step of the way. Just going up and down the stairs to our apartment was a harrowing exercise.

But I never had a moment’s doubt that once His Holiness returned, things would get better. Exactly how, I had no idea. But I needed some quality time with the Dalai Lama. Just the two of us together.

The mood in the Dalai Lama’s dining room that lunchtime was the same as it always was when he entertained visitors, his guests instantly responding to his lightness and spontaneity, his capacity to inspire their own benevolence. Social media gurus, contemplative neuroscientists, lamas and psychologists exchanged ideas, while savoring a delicious meal prepared in the kitchen downstairs by the two women who had become institutions in His Holiness’ household—the voluble and larger-than-life VIP chef, Mrs. Trinci, and her beautiful daughter, Serena.

Apart from the Dalai Lama, my biggest fan at Namgyal from my earliest days had been Mrs Trinci. Italian, operatic, her arms clanking with gold bracelets, she had showered me with delectable culinary treats, pronouncing me to be The Most Beautiful Creature That Ever Lived, a title to which many others would be added in due course—not all of them quite so delightful.

Following a heart attack, and on her specialist’s advice, Mrs. Trinci had come to the Dalai Lama for personal meditation lessons, over time becoming a mellower and less frenetic version of her former self—though no less a big-hearted one. When her daughter, Serena, had arrived back in Dharamshala after years working in some of Europe’s most famous restaurants, Mrs. Trinci had begun to share the burden of her work as His Holiness’ Executive Chef. Little did I know that, once drawn into Serena’s world, the most intriguing revelations of my life would be uncovered.

Elegant and graceful, long dark hair sweeping straight down her back, since the moment I first caught sight of Serena, I’d been captivated by her compassionate energy. As well as helping her mother take care of the Dalai Lama’s VIP guests, she had become co-manager of The Himalaya Book Café, along with its owner, Franc. We had instantly become firm friends and, from a variety of shelves, nooks and gateposts, I had witnessed the blossoming of her romance with the handsome and luminously intelligent Indian businessman she had met at yoga class—a man whose natural modesty concealed the fact that he just happened to be the Maharajah of Himachal Pradesh.

Serena had moved in with Sid—short for Siddhartha—once he had renovated a sprawling, colonial, mountainside home for them. Their home just happened to be a short walk away from my windowsill at Namgyal Monastery.

In time, I became aware of a strong connection to Sid; also to Zahra, his seventeen-year-old daughter—Sid’s first wife having died in a car accident many years before. Zahra lived away from home at boarding school, returning home for holidays. From the very first time I’d caught sight of Zahra I had adored her, and I loved spending time at their home.

As was the case at all lunchtime meetings with the Dalai Lama, my own needs were not overlooked. Head Waiter Kusali brought a ramekin to where I sat on the sill. Today’s meal was a casserole with the most deliciously thick gravy. As I lapped it up with noisy relish, several Silicon Valley executives glanced my way with expressions of amusement. During the meal, His Holiness looked at me several times too, but with a different expression. Even though we had spent almost no time together alone since his return, he seemed to sense that all was not well in my world.

Finishing my meal, I washed my face—even grooming had become difficult with such painful paws—and settled down, waiting for the gathering to come to an end. I felt a bit better with a tummy full of Mrs. Trinci’s delicious food.

But I still longed for the moment when I would have the Dalai Lama to myself.

Finally the guests were leaving, Tenzin and Oliver ushering them out of the room. His Holiness had already asked Dawa to pass on his compliments to the chefs, and to invite them upstairs so he could thank them personally, in what had become a delightful tradition. No sooner had the guests left than Dawa returned with a message.

‘Mrs. Trinci has already left, Your Holiness,’ he announced.

‘And Serena?’

‘She says she was only helping her mother, so can’t claim any credit for the meal. And she knows you’ve been away for a long time so is sure you must be very busy.’

The Dalai Lama nodded. It was by no means the first time an invitation to say ‘thank you’ had been rebuffed, even if in the most diplomatic way. For some time His Holiness remained in his seat with a thoughtful expression—was he perceiving something that eluded me?—before looking directly at me. Getting up he said, ‘I think we should go to see her, don’t you Snow Lion?’

As he made his way to the door, I hopped down from where I’d been sitting, bracing myself for the inevitable pain of landing. We walked through the apartment and into the corridor that led past the Executive Assistants’ office. I tried my best to tread normally, even though each step was more painful than ever. Walking on my back paws, in particular, was pure torture.

We headed down the stairs and along a short passage to the VIP kitchen. His Holiness paused in the doorway, watching as Serena busied herself in the kitchen. Today’s meal may have been over, but another was planned for a private visit by the Aga Khan in three days hence, which was the cause of much activity. Serena was opening cupboards, checking their contents, referring to a list, writing down items that needed to be stocked and going through the deep shelves of the fridge. She was so preoccupied that it was a while before she looked up and discovered she was not alone.

‘Oh! Your Holiness!’ As she folded her palms together at her heart, she flushed.

‘My dear Serena!’ The Dalai Lama walked over and gave her a hug. Glancing down, she saw me at his feet.

‘And I see little Rinpoche came downstairs too,’ she observed as they broke apart.

‘The meal was wonderful!’ The Dalai Lama gazed at her closely.

‘Thank you.’

‘Especially the main course.’

‘Vegetarian stroganoff. It’s the gravy that makes it.’

Long hair tucked under a chef’s hat and not wearing any make-up, this Serena looked very different from the one who worked front of house at The Himalaya Book Café, or who ran her spice pack business from the office above the café. But more than that, today there seemed to be a tension in her face, a concern clouding her eyes.

‘I am never too busy to see you,’ said the Dalai Lama. ‘But perhaps you are too busy to see me?’ There was humor in his expression, but also concern.

His Holiness had known Serena since she was a little girl. Mrs. Trinci, who had been widowed at an early age, had brought her in to do her homework at the kitchen bench, while she got on with meal preparation. In those early days, way before my time, I’d been told how Serena was drawn to the Dalai Lama, so that he’d become like a father figure to her.

She may have spent over ten years in Europe, making her own way in the world, but when she’d returned to Dharamshala, her bond with His Holiness had been as strong as ever. They were like family, and he knew her every expression, which was why she had to break away from his gaze.

‘I’m sorry, Your Holiness,’ she said. ‘I didn’t mean to cause offence.’

He shrugged indicating that this wasn’t the point.

Looking back at her list and to the cupboards she admitted, ‘I am pretty stressed at the moment.’

‘The Aga Khan lunch?’ queried the Dalai Lama.

Serena brushed away the suggestion. ‘No. Nothing to do with that.’ Swiveling away, she looked round the kitchen, everywhere except at him. Then chewing at her lip, she said somewhat reluctantly, ‘It’s the business.’

‘Very busy?’ His Holiness’ tone was sympathetic.

‘Not busy enough.’ She shot him a glance. ‘As you know, we did a roaring trade when we first started out. We doubled in size each year for the first three years. But we’ve hit a wall.’

The spice pack idea had come about when tourists asked about the delicious sauces, marinades and seasonings which made their meals at The Himalaya Book Café so utterly irresistible. Consulting with the café’s resident chefs, Nepalese brothers Jigme and Ngawang Dragpa, Serena had devised ways to package spice blends that could be delivered globally by mail order. When Sid had opened doors to local spice producers at wholesale prices, suddenly they were in business.

Beautiful branding and an efficient delivery service soon had The Himalaya Book Café Spice Packs heading out to the four corners of the world. And after Sid and Serena were married two years ago, they decided that all profits from the business should be used to support local youngsters get the training they needed to find work.

‘You are worried for the children?’ the Dalai Lama queried.

‘There are so many of them!’ Serena’s voice rose. ‘And they’ve come to depend on us. We’re their last chance!’

In a moment she had become as impassioned as Mrs. Trinci herself—a resemblance I’d seldom witnessed before.

‘And the sales …’

‘Nosedived!’ she was emphatic. ‘Back to where they were twelve months ago. Eighteen, even!’ Unable to stand still a moment longer, she strode to the other side of the kitchen to collect her handbag. Unnecessarily. Before bringing it back and dumping it beside her list with a thud.

‘It’s not just one thing that’s affecting our business, it’s so many,’ her dark eyes blazed. ‘It’s consumer fatigue. And massive competition. We’re being regulated out of business in some markets. Only last week this new biosecurity law came in and we lost all our customers in Australia.’ She flicked both hands open, palms facing upwards. ‘Overnight!’

I looked up at the Dalai Lama. This was not the Serena I thought I knew. I had never seen my friend—whose name had always seemed so appropriate—in such a state. As I observed His Holiness, I sensed that he understood much more about what was happening. And for the first time I had an inkling that perhaps there was a deeper cause for Serena’s frustration. That what she was talking about was only a proxy, a substitute for another cause of anguish.

‘All the while …’ she was gesturing outside, ‘our waiting list for kids needing basic IT skills just keeps getting longer and longer!’

Jaw tense, with a vein standing out on her neck, she seemed at the end of her tether. ‘I look at their little faces and I know how much they need my help, but I just don’t seem able to turn things around!’ She raised her hands to her head. ‘We’ve tried everything that might make a difference! You think something’s going to work. Other people swear by doing this thing or that thing. You build up your hopes because you so desperately want it to come right …’

Suddenly she seemed to crumple, her shoulders slumping. Her eyes welled with tears. She turned to face the Dalai Lama, her face a portrait of misery. ‘I just feel like I’m failing everyone,’ she said.

His Holiness didn’t say anything for a moment, simply stood and enveloped her in his benevolent attention.

‘Sid especially,’ she said softly, glancing towards me with the warm-eyed glow of maternal feeling, which I was more familiar with.

Suddenly I understood what I sensed His Holiness already had. And it was as if, in that moment, a shift occurred in the room, so that we all knew what was really being discussed without the need for it to be made explicit. The deeper cause of Serena’s torment.

When Serena had married Sid they’d made no secret of their wish to have a family together as soon as possible. Many of their friends had expected an announcement of that kind to follow within months. Two years later, none had been made.

‘You have spoken to Sid?’ asked the Dalai Lama softly.

‘We talk about it all the time.’

‘He doesn’t feel you’re … letting him down?’

She shook her head miserably. ‘You know Sid. He’d never say that. He’s too much the gentleman.’

The Dalai Lama took one of her hands in his with the utmost gentleness. ‘Often, our greatest suffering is self-inflicted.’

‘Self-inflicted?’ Her eyes widened.

‘Perhaps because of attachment.’

Serena’s expression turned to one of hurt. ‘It’s not like I’m desperate for a Maserati!’

‘No, no,’ His Holiness shook his head. ‘Material things are only one source of attachment. A more frequent cause is attachment to outcomes.’

‘Outcomes?’

‘To having things the way we want them.’

‘What if it’s not just about me?’ she objected, pulling her hand quickly out of his. ‘What if it’s other people I’m concerned about?’

‘This is not a moral judgement …’ he tried to reassure her.

‘Sounds like it to me!’ she snapped. ‘Sounds very much like a judgement!’

Striding over to the counter, she grabbed the list she’d been making and threw it in her handbag. Tugging off her chef’s hat, she tossed it towards the sink.

‘You know, this is exactly the kind of conversation I didn’t want to have …’ she told him, eyes blazing. ‘It’s why I didn’t come upstairs. I don’t need to be told that it’s all in my mind. That if I change the way I think, then everything will be hunky-dory. Sometimes life is just shit—and that’s all there is to it!’

With that, she strode out of the kitchen, grabbing the door as she left and slamming it behind her.

I stared at the door, shaken by what I had just witnessed. In the seven years I’ve lived with the Dalai Lama, no-one had ever stormed out of his presence, much less banged the door as they left. And the very last person in the world I would have thought would do so was serene Serena.

His Holiness reached down to stroke my neck. ‘Such suffering,’ he observed, softly. ‘May she soon be free of anger and attachment.’

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

That afternoon, the Dalai Lama was officiating at the ordination of monks across the courtyard at the temple. I remained on my sill, dozing and waiting for the moment when I’d finally have some time alone with him. And as I waited, the kitchen scene replayed in my mind: Serena’s misery. His Holiness’ attempt to help. Her raised voice and the slammed door.

Anger and attachment, the two things he had wished her to be free of, were considered delusions in Tibetan Buddhism—a delusion being any mental factor that disturbs one’s peace of mind. Both were said to arise from the same underlying cause: the belief that things, people or situations possess inherent qualities which make them desirable—in which case we want them; or undesirable—in which case we do not. I had sat through countless hours of the Dalai Lama explaining these basic principles to people. And Serena was as familiar with them as anyone.

When it came to applying them to everyday life, however, things weren’t always so clear cut. Serena’s peace of mind was disturbed—of that, there was no dispute. But what if her unhappiness hadn’t been caused by thinking about herself? Instead of being self-inflicted, what about pain arising from concern for others? What did Buddhism have to say about that?

What’s more, wasn’t the wish to have a baby not an entirely natural, feminine instinct for many, something which flowed deeper than thought or concept? What if, on this occasion, His Holiness had got it wrong?

As it happened, I didn’t have long to wait to learn the answer. As dusk fell over the Namgyal courtyard, His Holiness returned home. Tenzin came to switch on the lamps in our apartment and had gone to fetch His Holiness a cup of green tea, when there was a familiar knock on the door. We both looked up.

‘I’m so, so sorry!’ It was Serena, ashen-faced and tearful. ‘I don’t know what came over me!’

Stepping over from the other side of the room, His Holiness gestured towards her and began to chuckle. ‘You!’ Then he pointed at his door and acted out slamming it. ‘Boom!’

Shaking her head, she looked bereft. ‘Can you ever forgive me?’

He opened his arms and she came towards him. As they embraced she began to say, ‘I just want you to know …’

‘Yes, yes.’ He interrupted, patting her back. ‘Words are not necessary.’

A short while later, Tenzin had brought them both tea and they were seated, facing each other across a table. ‘I know you said it’s attachment that’s causing me pain,’ began Serena.

The Dalai Lama looked at her quite sternly. ‘No judgement,’ he said.

‘I’m just wanting to understand.’ She paused, trying to order her thoughts. ‘I really do want to help others—like these kids who need training. And I’m doing all I can to make the business work for them. So how is it possible not to be attached?’

His Holiness smiled before saying simply, ‘By understanding that your peace of mind, your wellbeing, does not depend on it.’

She absorbed this in silence, before tilting her head. ‘That just sounds a bit cold. Lacking in compassion.’

The Dalai Lama raised his eyebrows. ‘Compassion is the wish to relieve beings of suffering.’

‘Yes.’

‘Are we better able to help others when our minds are calm and ordered, or when there is great turmoil?’ His hand motioned the rising and falling of waves.

Serena inclined her head.

‘For the sake of self and others, if we wish to practise effective compassion, we need a calm mind,’ he said. ‘This is essential. What’s more, non-attachment is in accordance with the truth.’

Leaning forward in his seat, he studied her closely for a while. ‘I remember a time, you had just come back from Europe.’

Serena smiled.

‘You were home in Dharamshala. No job. No—what do you say—boyfriend?’ he chuckled.

‘One of the happiest times of my life!’ she volunteered.

‘Very happy, even though you weren’t helping any children get computer skills.’

She was shaking her head. ‘I hadn’t thought of any of that back then.’

‘You see. No outcome. But still, very happy. The two,’ he held his hands palms facing upwards, some distance from each other, ‘have no relationship. Only when we invent a relationship, there is a problem. When we say, “I can only be happy when this happens” or “I can only feel peaceful if that happens,” that’s when we make a problem for ourselves.

‘Attachment is when we believe that a person, a thing or an outcome is necessary for our happiness. At that moment, we turn the person, thing or outcome into a source of future suffering. We risk becoming enslaved to it. Much better to think: I am already the possessor of happiness and inner peace. To have this person, thing or outcome in my life—how wonderful! But it is not necessary for my fundamental wellbeing.’

Serena was nodding slowly.

‘And I will tell you the secret gift of non-attachment,’ the Dalai Lama’s eyes sparkled. ‘When we are able to hold an outcome in our heart with genuine non-attachment, then it is much more likely to happen. Clinging with attachment not only causes misery. It also makes us less successful.’

Following his every word closely, Serena asked him, ‘Even when it comes to falling pregnant?’

‘Of course!’ The Dalai Lama nodded, as though this was a statement of the obvious. ‘For you at the moment, too much stress.’

‘I have found myself worrying a lot lately. So many horrible things have happened, all in a short space of time.’

‘Then it is time for renunciation,’ announced His Holiness, ‘time to turn away from the true causes of your unhappiness.’

‘Which are not the spice pack problems. Or … this’ she touched her abdomen. ‘But attachment to how I’d like things to be?’

‘Exactly. Renunciation is when you decide you’ve had enough. When you finally recognise that your unhappiness isn’t coming from out there, but from your own mind. From battling the way that things are, and wishing them to be different. Renunciation is when we turn away from the suffering we are experiencing because of our attachment to the way we think that things should be, or perhaps bitterness about the way they are. You could say that renunciation is the start of our inner journey. Instead of fixating on external circumstances, we look within.’

‘In my heart I think I’ve known that I needed to let go.’

‘Let go. Let go,’ agreed His Holiness. ‘The more we let go, the more peace here.’ He touched his heart.

Serena regarded the Dalai Lama with an expression of gratitude. Then she stood up. ‘Now, I should let go of you. I’ve already taken up too much of your time today.’ Glancing towards the sill, she saw me lying on my side, watching them. ‘I’m sure you’ll be wanting some quality time with little Rinpoche,’ she said.

As His Holiness rose from his chair, Serena stepped over to stroke me. Responding, I reached out both arms and legs, intending a full, tremulous, tummy stretch. But as I extended, my front, right claw caught on her wedding ring. Searing pain jolted through my whole side. I recoiled in agony.

‘Rinpoche!’ Serena was aghast, as I let out a yowl.

Bending, she studied my paw closely. At the same time, the Dalai Lama leaned over me too. Both caught sight of the same thing at the same time. His Holiness’ eyebrows shot up in alarm. Serena’s forehead furrowed in concern. ‘Oh, you poor little thing!’ she wailed. She turned to the Dalai Lama, ‘Look at the length of them.’

He was shaking his head. ‘I thought the way she was walking this afternoon was not quite right.’

‘All these weeks you’ve been away, and nobody looking out for her.’

‘We must take action.’ His Holiness’ expression was serious. ‘Immediately.’

I, dear reader, am not a cat who takes kindly to being held fast while having her claws trimmed. Even when the person doing the holding is the Dalai Lama, and the person doing the trimming is the Maharani of Himachal Pradesh. But no matter how much I writhed and wriggled, there was no escaping His Holiness’ clutches. No evading the stainless steel blades of Serena’s trimmers. One by one they worked their way round each of my paws until every last nail had been pruned.

As soon as they put me down, I stormed towards the Dalai Lama’s desk as fast as my grey boots would take me, ears firmly pressed back. The desk was my place of safety. Under it, I was inaccessible to a human arm. Even as I made my way over, however, I became aware of something: the pain in my paws and legs had gone. Completely. There wasn’t so much as the merest twinge of discomfort.

I inspected my paws by licking them. As I did, I realized that, bit by bit, I must have become used to my nails protruding. They had grown a little, then a little more, and I had become so accustomed to them being the way they were that I’d ignored them.

Serena was returning the trimmers to her handbag and preparing to go. ‘The greatest suffering is self-inflicted. Isn’t that what you were saying this morning?’ her tone was wry. ‘And even when you try to help …’

Peering up between the legs of the desk, I saw His Holiness pretending to be me, lashing out one of his arms, fingers outstretched. Before segueing to a door slam. ‘Bang!’ he laughed. ‘Same, same.’

Surely not! I was indignant. You couldn’t possibly equate the two. Could you?!

‘Is it possible to become attached to attachment?’ Serena asked, hitching her bag over her shoulder.

‘Oh yes,’ said the Dalai Lama. ‘Sometimes the things we cling to most tightly are those that hurt us more than anything. But we keep on clinging because we don’t believe there’s a different way.’ Turning pensive, he murmured, ‘This is the great sadness of samsara. A person can be starving in a room, even though just along the passage, there is a kitchen with all the food she could possibly eat. But she has to walk to the kitchen by herself. She has to believe that it’s there. There must come a time when she says, “Enough suffering, already! I must try something different.”’

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

There is a particular ritual with which His Holiness and I sometimes end the day. Before retiring to bed, he will go into his own small kitchen, furnished with just a few culinary essentials. There he will put a slice of bread into a toaster, before switching on the kettle to make himself a cup of tea.

If I haven’t already followed him, the aroma of toasting bread immediately summons me from wherever I am to sit at his feet, expectantly. Once toast is made—entirely for my delectation, as the Dalai Lama doesn’t eat in the evening—he will cut a small corner for me and coat it liberally with butter, before putting it on a saucer and placing it before me.

The two of us enjoy our time together, His Holiness sitting at a small table sipping tea, while I crunch my buttered toast with relish.

‘I am sorry I haven’t been here for you, my little one,’ he said tonight, once I’d finished my toast and looked up at him. ‘Your claws grew so long.’

He gazed at me thoughtfully, as I licked my right, front paw, relishing the way my tongue had free access to my velvet pads.

‘We humans also have to be vigilant, just like you,’ he observed, as I began washing my face. ‘Our thoughts are like claws. They can be very helpful when we turn our mind to things. Develop ideas. Set goals. Express emotions. But if we aren’t careful, these same thoughts can turn in on us and become the source of our greatest pain. They no longer help us take purposeful action, but instead are the cause of self-inflicted misery. Cat or human, we are the same.’

Reaching down, he lifted me onto his lap, took my front, left paw in his hand and turned it sideways, gazing closely at my newly trimmed nails. ‘When we’ve had enough suffering and want to make a new start, that’s renunciation,’ he said.

I fixed him with a sapphire-blue gaze of great devotion.

He leaned down to touch me with his cheek, murmuring softly, ‘You might say this is the first law—the first paw—of spiritual success. What do you think, little Snow Lion?’

When he put me back down on the floor I was struck by one of those bolts of energetic mania to which we cats are occasionally prone, especially after eating a scrumptious morsel. Even more so when feeling celebratory.

I hunched forwards. Shot a glance at him over my shoulder. Then bolted out of the kitchen, tearing down the corridor as fast as my fluffy grey boots would take me. It had been many weeks since I’d even thought of doing such a thing. And as I flew along the runner I was wonderfully liberated. Unburdened. Pain-free.

If this was how renunciation felt, how wonderful! I only wish I’d experienced the first paw of spiritual success a whole lot sooner!

At the door to the kitchen behind me, the Dalai Lama burst out laughing.

~ End of Chapter One ~

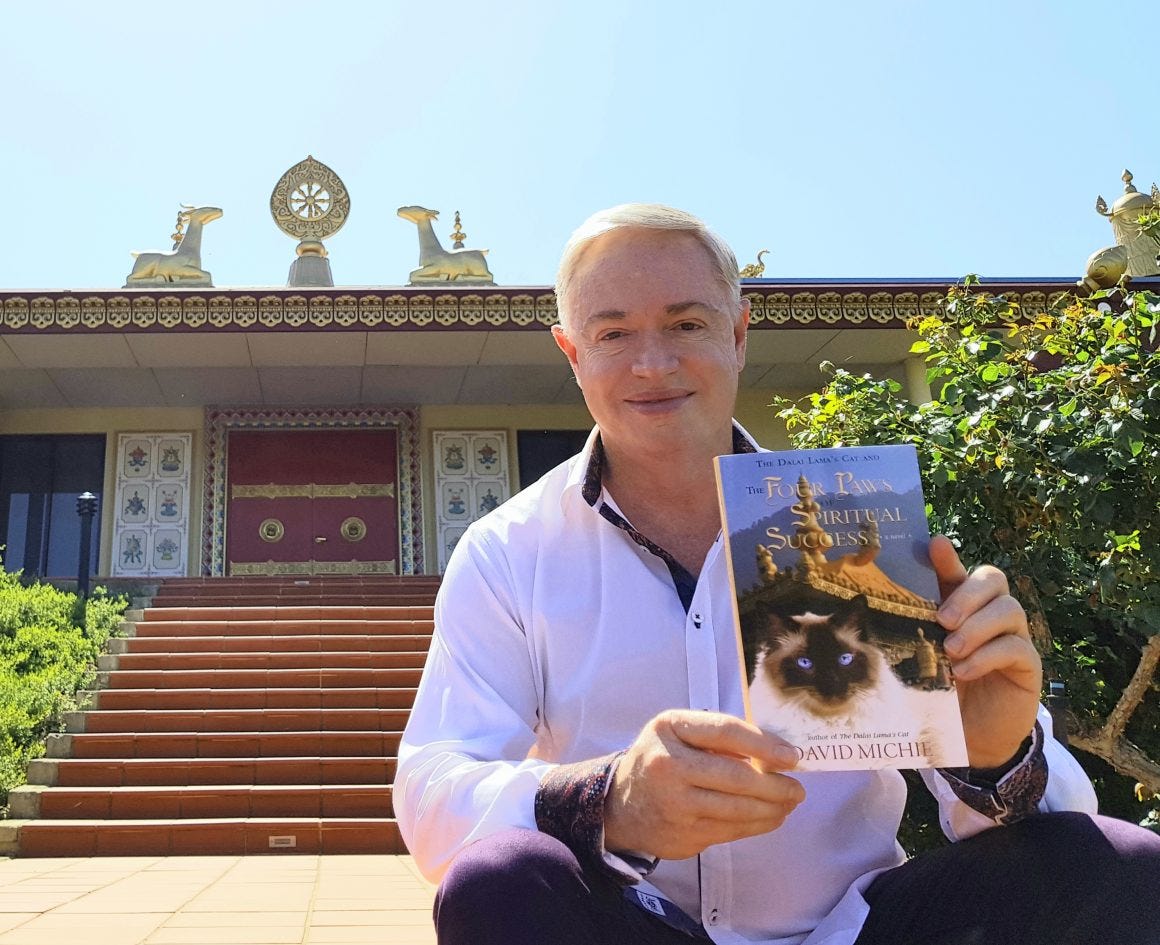

“The Dalai Lama’s Cat and the Four Paws of Spiritual Success” is available in paperback from Amazon. In Australia you can also order it from your local bookstore. Ebooks and audio CDs/MP3s, are also available from Amazon and via other major digital retailers including B&N, Apple and Kobo.

I hope you enjoyed the opening to The Dalai Lama’s Cat and the Four Paws of Spiritual Success. If you did, subscribe to me on Substack to get regular articles, guided meditations, book recommendations and other stimulating and useful stuff!

Here are a few other things you can also do if you choose:

Check out my other books which explore the themes of my blogs in more detail. You can read the first chapters of all my books and find links to where to buy them here.

Have a look at the Free Stuff section of my website. Here you will find lots of downloads including guided meditations, plus audio files of yours truly reading the first chapter of several of my books.

Join me on Mindful Safari in Zimbabwe, where I was born and grew up. On Mindful Safari we combine game drives and magical encounters with lion, elephant, giraffe, and other iconic wildlife, with inner journeys exploring the nature of our own mind. Find out more by clicking here.