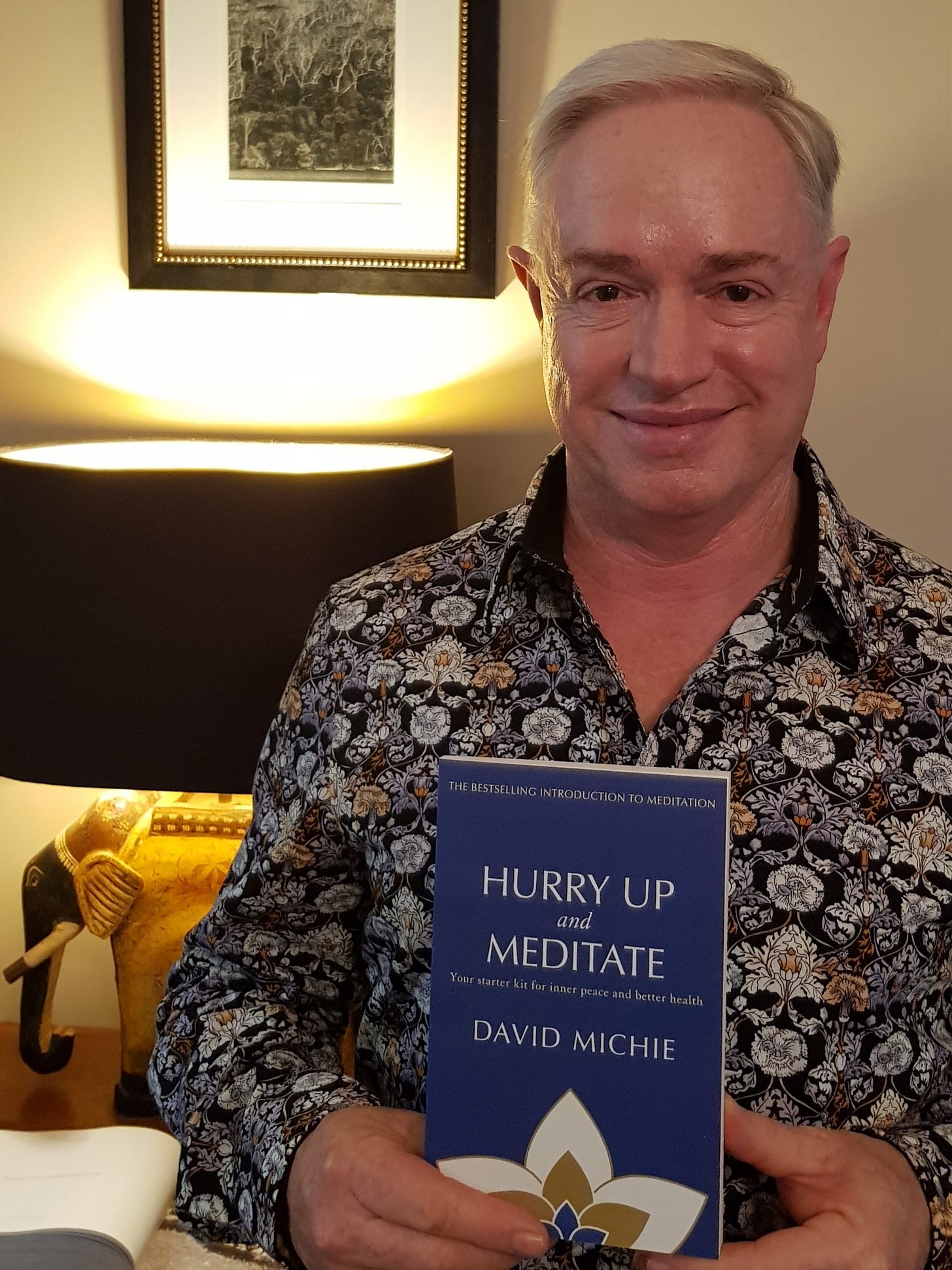

Read the introduction of 'Hurry Up and Meditate' here!

Introduction

I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestioned ability of a man to elevate his life by conscious endeavour.

Henry David Thoreau

Yes, it’s a deliberately provocative title. After all, being in a hurry is the opposite of meditating, isn’t it? If we have a lot going on in our lives, is it realistic trying to find even more time to meditate? The idea of infusing our daily schedule with newfound tranquillity may sound appealing-but not everyone is temperamentally suited to sitting around in the lotus position chanting ‘Om’. Not to mention the fact that some of us just have very active minds. We’d like to meditate-but we’re simply not capable of switching off.

Whoa! Back up a little! These are what I call the most common ‘buts’ of meditation-as in, ‘I’d like to meditate, but…’ And the amazing thing is that it’s exactly the people who use the ‘too busy’, ‘too hard’ and ‘too hyper’ justifications who stand to gain the most from meditation.

How can I be so sure of this? Because I was one of them.

This book has been written for people in a hurry, and its message is quite simple: meditation is probably the best chance you’ve got to combat stress, cultivate happiness, enhance your performance, realise your goals and attain mastery of your mental, emotional and material destiny.

Big claims, you may think-but they’re supported by compelling evidence.

The science of meditation

In recent years technology has made it possible to monitor the impacts of mental activity. Measurable, observable and repeatable studies, conducted by many credible researchers from a wide range of highly respected universities and medical centres, leave no room for doubt about the benefits of meditation. A summary of key studies is provided in Chapters 2 and 3 of this book, because they provide the motivation needed to begin and sustain this profoundly life-enhancing practice.

Once you’ve been meditating for a while, of course, you won’t give two hoots about scientific studies because you’ll have direct, first-hand experience of how good it feels to meditate- and how stressful it feels not to. Just as we don’t need scientific research to persuade us that a long cool drink is wonderful on a hot summer’s afternoon, once we’ve experienced the benefits of meditation on a personal level, the clinical whys and wherefores no longer seem so relevant. Though in the beginning, they have an important part to play in getting us motivated-and keeping us that way.

If I were to summarise the scientific evidence in just a couple of paragraphs, it’s probably fair to say that if meditation was available in capsule form, it would be the biggest selling drug of all time. Where else can you find a treatment regime which lowers blood pressure and heart rate, providing highly effective anti-stress therapy, without any side effect whatsoever? Which, in addition, not only improves immune function, leading to less chance of catching a cold or flu bug, but which also significantly decreases our likelihood of being struck by a life-threatening illness like cancer or heart disease? Which improves neural coordination and, over time, actually changes the neuroplasticity of our brains, making us more efficient thinkers? Which boosts production of DHEA-the only hormone known to decrease directly with age-thereby slowing the ageing process? Which can form a powerful part of any complementary treatment regime for cancer and other illnesses-a function so important I have devoted a whole chapter to this subject. And these are just some of the physical benefits.

Turning to matters of the mind, scientists have shown that meditation heightens activity in the left prefrontal cortex of the brain, which is associated with happiness and relaxation, helping minimise use of all those anti-depressants and anti-anxiety drugs which our society consumes in such terrifying quantities. Meditation improves concentration and activates gamma waves-the state of consciousness in which higher-level thinking and insight occurs. It improves our awareness of everything around us, including other people’s moods and feelings. It enhances our sense of zest, vitality and joie de vivre.

It’s worth mentioning at this early stage that the word ‘meditation’ covers a very wide range of practices and techniques, all of which have their own particular purpose and emphasis. This is explained more fully in Chapter 5, which provides a range of different meditation types to explore.

But all in all, any objective assessment of the effects of meditation, which are so powerful, so positive and so all-pervasive, can reach only one conclusion: if we’re not doing so already, we should hurry up and meditate!

Interestingly, the counterpoint to this is also true. If we want to hurry up-if we want to lead productive, fulfilled, well-rounded and happy lives-meditation is the rocket fuel we need to propel us. Not only can we find the resources to turbo-charge our performance, by cultivating meditation practices we can also begin to discover a new richness and beauty even in the midst of a busy daily schedule. We have the capacity to create a sense of inner peace and objectivity which not only makes life a lot more pleasant, but also helps us work towards our goals more effectively.

A personal story

While the scientifically established benefits of meditation are important, this book isn’t only about the empirical evidence emerging from laboratories. I’d also like to share my personal story, and if I come across as a tad evangelical, it’s because meditation is a subject close to my heart.

I’m a person in a hurry and I’ve been meditating for over fourteen years. Starting out as someone who couldn’t keep his bum on a cushion for more than a few minutes, I now usually end my one-hour morning meditation sessions wishing I didn’t have to stop. My concentration has moved from almost non-existent to much improved. And when I think of my lifestyle now versus ten years ago, there’s no comparison. Then I was a harassed mid-level executive, with very limited time or capacity to enjoy life. Now I find myself working less, earning more, and able to pursue the interests that fulfil me-such as writing books like this one.

Having said all that, I’m not making any grand claims about my meditation prowess. In many ways meditation is exactly like going to the gym or learning to play a musical instrument. No matter how good you get, there’s always plenty of room for improvement. The measure for comparison is not other people, but your own personal baseline.

It’s worth emphasising that to benefit from meditation it’s not necessary to begin with hour-long daily sessions, to adopt an austere lifestyle or to take off to the mountains for month long retreats. Even a few minutes of spot meditation, practised regularly, makes an immediate and appreciable difference to our everyday wellbeing.

I should also add that while meditation has been embraced, in different ways, by all the major religious traditions, this book is intended for use by people in a hurry, whether or not you follow a particular religion. The focus of Hurry Up and Meditate is not so much on belief systems as on improving mental and physical health. That said, the opportunity to invoke religious symbols may be useful to some readers, and I’ll be sure to refer to these opportunities.

For those readers who do follow a religious tradition, and may be anxious about how meditation fits in, I can think of no better advice than that given by Ian Gawler, the inspiring founder of The Gawler Foundation, who survived cancer against all medical expectations, and has gone on to help many thousands of cancer patients do the same: ‘While some people are apprehensive that meditation may conflict with their beliefs, the usual experience is that it leads to a heightened appreciation of their particular religious leanings and a greater level of personal joy.’

As a Tibetan Buddhist, I will draw on the rich meditative heritage of my own tradition. While Hurry Up and Meditate is not about Buddhism, it is my heartfelt wish that readers of my previous work Buddhism for Busy People will find in this book all the detail and understanding they need to make meditation the same profoundly life-enhancing practice that it has become for me.

Coming home

Just as golfers try to improve their handicaps and classical musicians work through their grades, meditators have a nine-level yardstick by which to measure their progress. It’s important to mention this early on, to correct the mistaken impression some people have that meditation is some kind of undirected, touchyfeely, ‘Hey man, you’ve just gotta, like, bliss out’ activity.

On the contrary, meditation prescribes rigorous methodologies which have been practised for well over two and a half thousand years. It involves discipline and hard work-and there’s a chance that at some point you may get so frustrated you’ll consider throwing in the towel.

But if you’ve been meditating properly, even for only a few months, you won’t be able to. At some point, perhaps with a sigh of resignation, you will once again resume your place on the meditation cushion because you’ll have discovered that meditation is the best way you know of coming home. This has certainly been my experience. And I know there is nothing very unusual about my journey so far. Speaking to other meditators, as I frequently do, it’s clear that while we all share the same challenges, we also experience the same life-changing benefits.

Ask a group of meditators why they started their practice and you’ll get a variety of answers. These won’t be expressed in scientific terms-I have never met anyone who said they meditated to improve their neuroplasticity. Instead you’ll hear about the benefits of meditation from a more subjective perspective.

Some people begin with a very specific intention: to support a battle against cancer or some other serious medical condition. To help restore a sense of calm after having been through a stressful life event, such as relationship or career trauma. As an aid to learning, particularly in preparing for important exams. And there’s no question that meditation can be an extremely powerful tool in all these cases.

But whatever the original starting point, it’s often the case that people discover benefits way beyond what they originally signed up for. Yes, meditation helps us get a grip on problems where they originate-in our minds-but it offers us far more than merely removing the negatives from our lives.

What exactly is good mental health?

In the same way that someone free from any diagnosable illness is not necessarily brimming with good health, just because we don’t suffer from depression or stress doesn’t mean we’re in especially good mental shape. Just as we need to apply some effort to keep physically fit, keeping mentally trim, taut and terrific is something we’ve got to work on. And arguably the best of all starting points is meditation.

What do I mean by being in good mental shape? A greater feeling of happiness is the most obvious benefit which keeps meditators coming back for more. A sense of deep-down inner peace and resilience, improving one’s ability to weather the inevitable storms of life. Enhanced concentration, enabling rapid processing of work and other tasks. A more outward-looking, panoramic perspective, providing the basis for greater equanimity in our dealings with others.

Whatever we wish to achieve in life, whatever our chosen path to self-fulfilment, meditation provides us with an extremely powerful tool, because through its practice we become more coherent, integrated and purposeful at all levels of behaviour.

And if we still don’t know what our path to self-fulfilment might be, meditation may help us find it.

Finding peace in the eye of the storm

Beneath the teasing title of this book is the suggestion of a much bigger question. As people in a hurry, is it also possible to lead a contemplative life? Can work deadlines, mortgage repayments, and complicated family and personal relationships combine with meditation and inner growth? Is it possible to find peace in the eye of the storm?

Of course, you already know what my response to those questions will be, so let me back it up with an explanation.

Among the most commonly prescribed, but still rapidly growing, drugs in the Western world are various classes of psychiatric drugs, be they anti-depressant, anti-anxiety, stress management, uppers or downers by whatever name.

In the UK, over 13 million prescriptions for anti-depressants are issued every year to an estimated 3.5 million patients. In the US over 8 million people are using anti-depressants, and even in Australia, which has an international reputation for sunny optimism, depression is now the fourth most common reason that people see the doctor.

So pervasive are psychiatric, not to mention non-prescribed, drugs, that most of us either have used them ourselves or know people who do. But the amazing thing is that when people take their daily anti-depressant or draw on their recreational joint, they do so without any expectation that it will result in a change to their external circumstances. Taking a Prozac is not a known cause for large and unexplained credits to appear in one’s bank account, or for one’s irksome boss to undergo a personality transplant. But users do expect to feel better about things. Implicit in the act of taking such medication is the acceptance that even if ‘reality’ doesn’t change, we can still feel a whole lot better about it by changing our mood, our pharmacological make-up, our interpretation of what is going on around us.

Which is exactly what meditation does-except without the toxic side effects. No one is disputing that even the most mentally robust among us may at some point in our lives benefit from pharmacological support. But for most of us, most of the time, why pump our bodies with mind-altering chemicals if we can get the same result, and a whole lot more benefits besides, through natural means? The most powerful pharmaceutical manufacturer is to be found not in the industrial sites outside our capital cities, but between our ears. Why not take control of our own built-in pharmacy to relieve stress, elevate mood and help manage illness?

So, to answer the question about whether or not we can combine tranquil contemplation with a helter-skelter lifestyle, the answer is not so much ‘we can’ as ‘we must’. If we’re leading frenetic lives, burning the candle at both ends, this is exactly why we need to cultivate inner calm. If others around us are agitated and stressed out, that’s precisely the reason we need to be more relaxed, positive and benevolent. We may not always be able to change the world around us, but we can definitely change our attitude towards it.

At a deeper level it is perhaps worth asking why, both collectively and individually, we feel the need to keep so busy, and why we so quickly become bored and lonely when we’re stripped of all the busyness and distraction with which we fill our lives. Nineteenth-century American poet Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote amusingly about the wish to escape from one’s self: ‘I pack my trunk, embrace my friends, embark on the sea, and at last wake up in Naples, and there beside me is the Stern Fact, the Sad Self, unrelenting, identical, that I fled from.’

1 Some people experiencing mood swings and milder forms of depression may be able to use meditation in place of medication. However, for people with a serious mental illness it is strongly recommended that you consult your doctor before starting meditation. With some conditions it may not be possible to stop taking medication, but meditation can be a very helpful additional support.

Are the circumstances of our lives that keep us so busy created entirely by others, or should we take some responsibility for them? What is it that makes us want to avoid a more simple, unhurried life-and can meditation provide the key?

Imprisonment or freedom?

A Buddhist monk I know used to hold regular meditation classes for prisoners. Over the years he got to know some of them quite well. Once he was asked by a group of lifers to describe a typical day in the monastery. Belonging to the austere Theravadan tradition, he explained how everyone had to get up at four o’clock in the morning for the first meditation session of the day, followed by more study and meditation classes throughout the morning. Lunch, the main meal, was eaten out of a single bowl-main course and any donated dessert all off the same plate-before the afternoon was spent doing manual work on the monastery property. There was no supper, just a cup of tea, and in the evening there was more study and meditation, which only ended around 10 p.m.

There was, of course, a ban on sex, alcohol, drugs, TV, newspapers, magazines and similar distractions. No money or personal possessions were allowed. Compared to prison, the regime he described was so harsh that one of the prisoners couldn’t contain himself. ‘You could always come and live here with us!’ he burst out in spontaneous sympathy, before realising what he was saying.

After the ensuing laughter had subsided, the monk couldn’t help reflecting on the paradox. His monastery with its strongly ascetic regime had a long waiting list of people who wanted to join as novices. And yet everyone in the very much more comfortable jail couldn’t wait to get out.

In other words, it’s not our circumstances so much as our feelings, beliefs and attitudes about those circumstances that make us happy or otherwise.

Have we arrived at our current lifestyle through freedom of choice? Or do we feel imprisoned in jobs or relationships from which we long to escape? Is our daily life an authentic reflection of our interests and values? Or merely a series of burdens and responsibilities from which we wish we could break free?

You may be wondering how meditation can help in any of this. Well, to quote the well-worn business adage, you can’t manage what you don’t monitor. If we don’t keep regular track of our income and expenditure, how can we possibly stay on top of our personal or company finances? If our goal is to lose weight and we don’t monitor how much we eat and how much we exercise, how can we be sure that calories out exceed calories in?

In the same way, changing our interpretations of the world requires us to be aware of what our current interpretations are. Meditation provides a direct support by helping us develop improved levels of mindfulness of our thoughts. By identifying our current mental habits we can start to replace ingrained negative mental patterns with more positive ones. Even a small improvement in mindfulness can help create very important change. Little by little we can turn our prisons into monasteries.

Masters of our own reality

Understanding of process enables a person to gain control of that process or to gain freedom from being controlled by it.

The Dalai Lama

As technological advancements enable neurologists to study the workings of the mind in greater detail, we are seeing a wonderful convergence take place. Ancient meditation-based wisdom and contemporary science are drawing together. We are coming to understand that our sensory awareness-such as sight-has as much to do with mental functioning and the way we interpret stimuli as it has with our sense receptors. We are gaining new insights showing how pleasure or pain is as much a result of our conditioning as our circumstances. Very recent studies confirm that we have it in our power to cultivate positive states of mind, and even change our neural pathways to enjoy happiness on a more ongoing basis. In short, contemporary research is affirming the ancient wisdom that we are the creators of our own reality.

If we don’t like the way we feel, we have the power to change it. We don’t have to wait to be rescued by a shift in external circumstance. Whether we are aware of it or not, we are the shapers of everything we are experiencing today, the co-authors of our mental continuum way into the future.

Which presents us with a simple choice. We can focus all our efforts on trying to manage an external reality in the hope that our deepest wishes are realised, our lives fulfilled, and we will never have to face any serious hardship (yeah, right!).

Or we can take charge of our own mental destiny.

It’s no simple choice because the meditative path is not an easy one. But how often are great things accomplished without effort?

More important is the knowledge that with perseverance, an open heart and clarity of purpose we can achieve profound inner transformation. If we choose, we can change our experience of reality so that our happiness is less conditional on the quirks of circumstance, and instead becomes an abiding presence. We can replace our short-term concerns with a more panoramic sense of destiny beyond anything we might currently imagine. We can celebrate a more transcendent understanding of who we are and why we’re here.

To begin, all we need is a small cushion, a quiet room-and a strong sense of adventure!

I hope you enjoyed the introduction of Hurry Up and Meditate. If you did, subscribe to me on Substack to get regular articles, guided meditations, book recommendations and other stimulating and useful stuff!

Here are a few other things you can also do if you choose:

Check out my books which explore the themes of my blogs in more detail. You can read the first chapters of all my books and find links to where to buy them here.

Have a look at the Free Stuff section of my website. Here you will find lots of downloads including guided meditations, plus audio files of yours truly reading the first chapter of several of my books.

Join me on Mindful Safari in Zimbabwe, where I was born and grew up. On Mindful Safari we combine game drives and magical encounters with lion, elephant, giraffe, and other iconic wildlife, with inner journeys exploring the nature of our own mind. Find out more by clicking here.