Quite a few readers responded to my recent post about karma - Does karma ever ripen in the same lifetime? – by asking about practices to purify negative karma.

Tibetan Buddhism brims with ‘opponent practices’ – i.e. methods to replace negative, self-harming patterns of thought, speech and action with positive, life-enhancing ones. Purifying negative karma is an important part of this process.

Specifically, the four opponent powers are well documented and widely practiced. In this post I will quote instructions offered directly by my own precious guru Geshe Acharya Thubten Loden in his book Path to Enlightenment in Tibetan Buddhism, Tushita Publications, Melbourne, Australia 1993. I will also provide some personal commentary.

I hope you find these practices as sensible, detailed, and personally liberating as I do.

Ideally, we would be listening to this Dharma while sitting in a temple at the feet of our much-loved and revered guru. We would have cultivated a settled state of mind such that the instructions would have the greatest possible impact.

Before reading further you may like to take a few moments to close your eyes, take a few nice, deep breaths, and let go of all distractions, before we venture forward together with calm minds and open hearts.

It may be helpful to begin with the reminder that karma is not something that exists anywhere except in our minds. In the West, with our fixation on the external material world, we have a tendency to think that reality is all going on ‘out there.’ When karma comes up in conversation it tends to be in a sensational context. A traffic accident or a financial windfall that happens to someone we know about may prompt the sage nodding of a head, along with the comment: “I guess it was her karma.”

This idea of karma is simplistic. The same accident may befall two people, and their experience of it will be quite different. One may come to think of it as the best thing that ever happened to them, because while lying in a hospital bed they met the doctor who became the love of their life.

Ditto, the same with a windfall. The first winner of Britain’s National Lottery in 1994 found that his eighteen-million-pound win made him a pariah in his Muslim community who shunned him as a gambler. His marriage broke up soon afterwards, he had a roller-coaster life and he died young of kidney failure, cirrhosis of the liver and heart disease.

It is our beliefs, interpretations and patterns of thinking that propel us towards happiness or unhappiness much more forcefully than any accident or lottery win. Those external events are, in Buddhist terminology, merely ‘contributing factors.’ Psychological studies by Dr Richard Davison and others confirm how we all have a ‘set point for happiness’ to which we revert after whatever dramatic ups or downs we may experience.

The deeper question is: how to move that set point in a positive direction. In the context of karma, in particular, how to get rid of the negative mental dynamics? The guilt and self-reproach? Craving and fear that we’re missing out? Rage at other people’s diabolical behaviour? Feelings of being worthless, helpless, pointless? To name only a few!

Open admission

Purifying negativities is preceded by openly admitting that we have them. Just as a visit to a psychologist benefits us most when we take full ownership of our own behaviour, the four opponent powers requires the same frank acknowledgment. We don’t need to divulge all our shortcomings to anyone else. Other people’s attitudes and judgements are beside the point. What we do need to be is open and honest with ourselves, however painful this self-exploration may be.

I know that some readers asking about purification feel awful about a particular relationship, action or pattern of behaviour in their past. Which is an excellent starting point! But don’t let’s restrict ourselves to that alone.

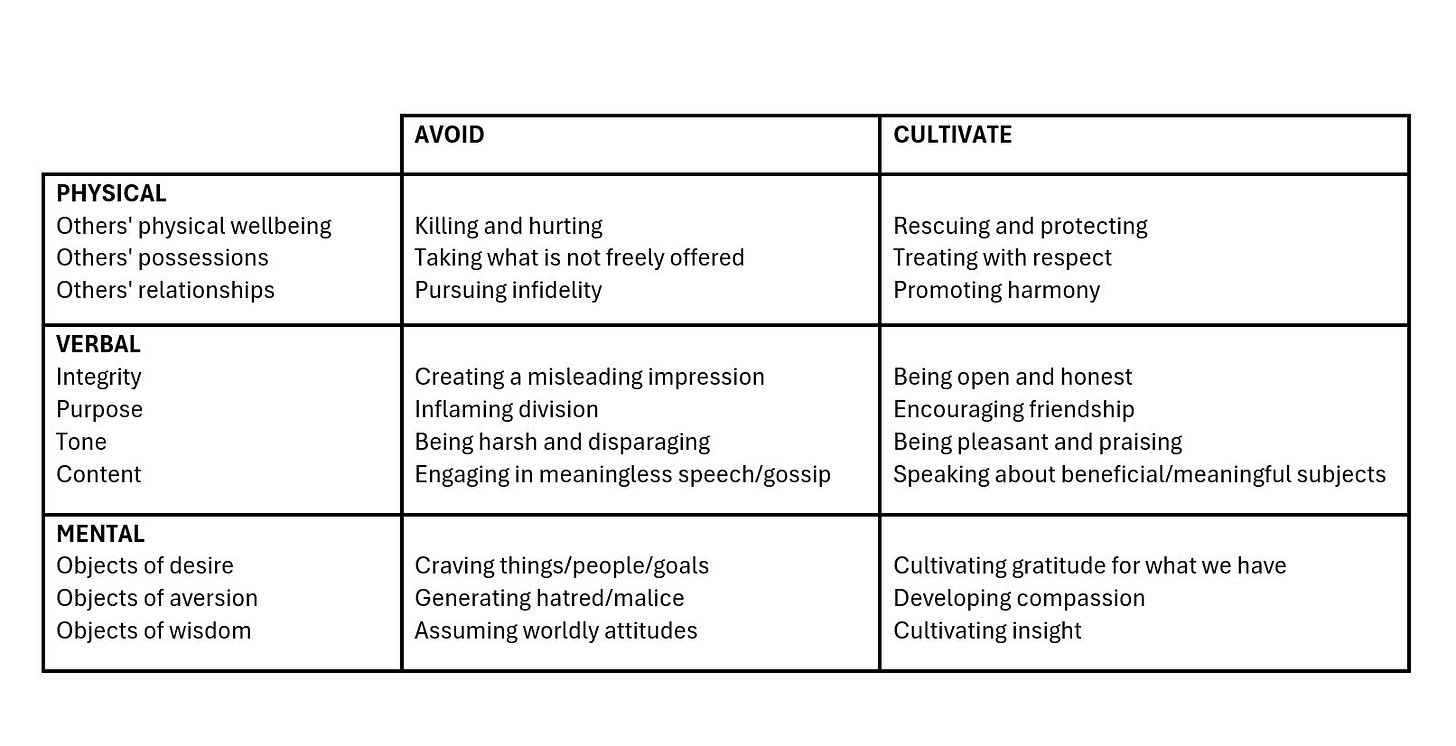

Buddha outlined ten virtues and non-virtues which I described in a recent post. Below is a table from that post providing an outline we can use for our personal review. Sitting quietly on my meditation cushion, going through this list in an unhurried, probing way and thinking about all I have done in my life, I have been startled by how much non-virtue I have created. And that’s only the stuff I can remember!

Many of us are accomplished practitioners when it comes to diminishing, conveniently forgetting or performing a variety of other mental gymnastics to help us feel that we are nicer, more virtuous versions of ourselves than our behaviour suggests!

When we openly admit our negativities of body, speech and mind, we attempt to do the opposite. The more rigorous, forensic and free from self-justification the better. We can’t fix something that we don’t acknowledge. So get it all out there! You may even want to write a list.

In the past, this process has been translated from Tibetan into English as ‘confession.’ For me, that term is too churchy or reminiscent of torture chambers to be helpful. I prefer ‘open admission’ or ‘acknowledgment.’

What we choose to label the process is unimportant. The main point is to have clarity about the breadth and depth of the negativities from which we wish to become free.

The power of the object

The first power means getting clear about just who our negative actions have affected. There are two broad categories of ‘object’: the first is the Three Jewels, namely, the Buddhas, Dharma and Sangha. The second is any other sentient being.

If this seems an odd basis on which to assign negative karma, bear in mind that these teachings originated in a very different context. Communities in the distant past were in constant contact with lamas, possibly regarded as Buddhas, their teachings, and enlightened fellow practitioners - the Sangha.

In our own case as so-called ‘householders’ two and a half thousand years later, the objects we are most likely to harm are other sentient beings. But if we have formally taken refuge and vows such as abandoning killing, stealing, and so on, we make ourselves accountable to these specific ethical standards in the invoked presence of the Buddhas. So when we break these vows by not walking the talk, we not only fail others, but the Buddhas too.

Eek!

What to do? Buddhism sees this all-too-predictable behaviour as akin to a person who has set out on a journey but who falls to the ground. Pragmatically, if we wish to continue we must get up, dust ourselves off, and continue on our way. In this analogy, the ground is the object. That object has power when, instead of rolling about helpless with remorse, we renew our commitment. In the case of first category objects, the Three Jewels, this means renewing our heartfelt refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. In the case of the second category object it means renewing our intention to attain enlightenment to best serve other beings. As summarised so often in our practice:

To the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha I go for refuge.

By the practice of giving and so on, may I attain Buddhahood to benefit all beings.

The power of regret

Having conducted a dispassionate analysis about exactly what we’ve done (open admission) and who we’ve harmed (power of the object) it’s time to consider how we feel about it.

“Regret purifies both negative karma and the tendency to create negative karma again,” writes Geshe Loden. “The extent to which you purify negative karma is dependent on the strength and sincerity of your regret. The strength of your regret depends on how clearly and extensively you see the disadvantages of non-virtue.”

From the outset it’s important to note that ‘regret’ has a quite different meaning from ‘guilt.’ I have been told that the Tibetan language doesn’t even have a word for ‘guilt.’ In our society, to feel guilty is to have a strong sense of a self who is unworthy. When we feel guilty there is little we can do except appeal to others: it is up to someone else, perhaps only the Almighty Himself, to forgive us.

Intelligent regret, on the other hand, is when we think of something we did and really wish we hadn’t. The traditional example is of the person who realises they have just eaten something to which they are strongly allergic. The logical response is to try to throw up, go to the hospital, or take other swift action before otherwise inevitable anaphylactic shock. In this scenario, we are the ones who must act.

To quote Geshe-la again: “Reflect on your negative actions: those arising from attachment, anger, ignorance and so on, created in the past, present or likely to be created in the future. Also recollect those negative actions that you have induced others to create. Then develop strong regret by recognising the suffering that your negative karma has brought and will definitely bring in the future, both for yourself and others.”

I find it especially relevant that Geshe-la specifically mentions negativities we are likely to create in the future. In this is the acknowledgment of patterns, habits, addictions from which it isn’t easy to break free. The Four Opponent Powers represent a process, an ongoing journey, rather than a “with a single bound they broke free” type exercise.

Having induced others to create negative karma is also worth pausing on. The karmic burden of killing that falls on such people as drug lords is said to be double that of the people they order to do the killing for them, because they have forced someone else to create such negativity. Correspondingly, inspiring others to be the best selves, creates greatly multiplied virtuous karma.

The power of the antidote

“The third power is a virtuous action done as an antidote for whatever negative action you wish to purify,” continues Geshe-la. “It can be any positive action performed with sincere regret for the negativity. You may, for example do prostrations, recite mantras, read Dharma texts, meditate on emptiness, recite the names of Buddhas, make offerings or practise generosity. Doing any of these with bodhichitta motivation and awareness of the emptiness of inherent existence of the subject, object and action makes the purification most powerful. Any practice of meditation (my emphasis) will purify negative karma, especially if you concentrate on bodhichitta or the wisdom perceiving emptiness.”

As often observed, the Dharma is the opposite of a one-size-fits-all tradition. The range of antidotes/opponent forces/remedial actions that we can undertake reflects our range of individual temperaments. Some people become practiced meditators. Others are much more motivated by going out in the world to help others.

What Geshe-la makess clear is that it really doesn’t matter what opponent force we choose, so long as we do it with the right motivation – i.e. sincere regret coupled with bodhichitta motivation and ideally an awareness of shunyata.

We can’t undo the cruel things we have done. Unsay the lies we have spoken or divisive and harsh things we have said. Nor can we unthink the extraordinarily destructive thoughts we have all had. What we can do, however, is antidote them - which is to say, become accomplished practitioners of their opposite.

Returning to the table above, if we have killed and physically harmed others, the antidote is to rescue and protect life. We may need to get creative about how we do this depending on the community we live in. For example, if we are feeling regretful about ignoring our vulnerable elderly mother who has since passed away, what about becoming a care home visitor? It may be too late to help our mother, but there are other mothers we can help. There is no shortage of opportunities to help others.

What we are seeking is a change of mind and heart. The ending of negative mental patterns and very intentional cultivation of new ones. Antidotes. As Geshe-la notes elsewhere, any act of virtue has ten times the power of non-virtue - an extraordinary cause for hope.

The emphasis Geshe-la puts on meditation is significant: any practice will purify negative karma, especially one with a focus on bodhichitta or the wisdom perceiving emptiness – shunyata. In our tradition there are some meditation practices designed specifically to purify negative karma, and I plan offering a guided meditation, based on The Heart Sutra, soon. Stay tuned!

The power of commitment

At the end of whatever purification practice we decide, we make the promise to ourselves not to perform the negative action again.

This suggestion comes with a proposed limited time horizon initially. Let’s say that we are prone to idle gossip. We recognise this, we regret it, but there’s a circle of friends who stimulate the behaviour and we aren’t ready to give up on them. In that case, we make a commitment to abandon idle gossip until next Saturday, when the group meets. When Saturday comes, we try our best not to get dragged into the usual gossipy discourse. Then we make a commitment until the following Saturday – and try again. With a more acute awareness of the dangers of gossip, over time it will become easier for us to abandon.

Our ultimate goal is to avoid having to put a cap on our commitment. In the meantime we avoid getting into the habit of making promises that we know we won’t keep. When we draw red lines around certain behaviours, but continually cross them, the red lines become meaningless. Rather make a commitment, if only to ourselves, that we know we can keep.

The 10 virtues and non-virtues presented in the table provide the basis of virtuous behaviour, and virtue equals happiness. You may find it helpful to copy the table and use it to review your own behaviour on a daily basis, with an initial focus especially on actions to be cultivated. To quote a business adage: “you can’t manage what you don’t monitor.” Becoming very familiar with the changes we are trying to make, being sure to celebrate our successes and using the energy of this happy recognition to move ever onwards and upwards - this is a whole practice in itself, deserving of its own post.

What we are seeking, dear readers, is nothing less than personal transformation. We are using our own regret to empower the most significant kind of self-development. We are taking personal responsibility to turn the mud in our lives into a lotus.

Ending the practice

Geshe-la concludes his instructions saying: “Purification is most effective if, at the end of the purification practice, you hold the feeling strongly that all your negativities have been completely eliminated and then meditate for as long as possible on space-like emptiness.”

This subjective experience of feeling purified is a strong point of emphasis. And it is no coincidence that we are invited to focus for some time on the primordial nature of our mind which is sky-like, pristine, and unblemished by whatever karmic clouds may pass through it.

Why is this visualisation so important? Because karma can only affect us for as long as we clutch at a separate sense of self. An inherently existent ‘me,’ or ‘I.’ When we let go of this conception - which in reality cannot be found - it is like removing the canvas from a painting. All that was painted on it, no matter how bold or elaborate, has nothing to which it can hold. The basis for karma, self-grasping ignorance, has been removed. You can’t paint the sky, lamas tell us. Put simply, karma cannot attach to something that isn’t there.

The following question is sometimes asked: I can’t remember all the negative things I have thought, said and done, even in this life. If I have lived since beginningless time, with no recollection of previous lives, how can I possibly purify all the negativities that exist in my mind stream?

Geshe-la explains that when a forest burns down, every living being within it is destroyed, whether we know about their existence or not. “In the same way, by grouping all negative karmas over all lifetimes and practising the four opponent powers in relation to them, all negative karmas can be purified without identifying each particular instance.”

“If the four opponent powers are applied strongly with sincere regret, a powerful commitment and so on, any negative karma, even the heaviest, can be completely purified. Applying them with medium strength, negative karma will be lessened. Even a weak practice of the four opponent powers will at least prevent negative karma from increasing.”

I hope you have found this post helpful. Speaking personally, purification has always been an important part of my Dharma practice and, until I attain enlightenment, always will be. The more familiar I become with that list of non-virtues, the more sensitive I become to my own less-than-virtuous actions during the day – and try to avoid them.

What’s more, the process of purification feels healing and cleansing. One has a sense of renewal, of starting over. ‘Be your own therapist,’ lamas exhort us. In becoming familiar with this process that’s exactly what we are doing. We know our own weaknesses and frailties all too well. Instead of brushing them under the rug, which is the usual temptation, lets use them to propel us a more transcendent reality.

Little by little, as we become more familiar too with the idea of shunyata, we begin to recognise – not only intellectually, but with a more liberating, spacious sense too – that the whole idea of inherently existent karma, a creator of karma and experiencer of it, are like so many clouds passing through the sky of boundless, pristine clarity that is, in reality, our true nature.

To explore other posts I have written on this subject you’ll find:

An explanation of the ten virtues and non virtues here;

My blog about the types of karma that can ripen in a single lifetime here;

Guilt v regret: a mouse-size musing by the Dalai Lama’s Cat herself here.

This has been a long post, and it could very easily have been a lot longer! Before you go I’d like to share just one, gorgeous photo of some of the beings you help support as a paying subscriber to this newsletter:

May all beings have happiness and the causes of happiness!

May all beings be free from suffering and the causes of suffering!

Brilliant David! This is one I’ll reread many times….perfect timing for a recent episode I’m handling better now….Thank you so much! So clearly written and simply beautiful teachings!

🙏 Bowing…Adrienne

My dear David,

Today I reread this blog and followed it as well as possible. I wrote my 10 lists, felt the regret, etc. Then I did the meditation. Oh my! I feel lifted and freed. Happy Juneteenth to all! (That's a US celebration of emancipation of slaves.)

Thank you so very much!