A couple of days ago I read a comment on a Facebook post by a woman who said that she made a point of never leaving home until she was in a state of mind to practice kindness. This humbling motivation was, however, quickly followed by a startling and dismaying statement. As a result, she said: I am frequently trampled upon, physical, verbally and spiritually. A doormat.

It’s often assumed that to be compassionate, to wish “to free others from suffering” - the Buddhist definition – your warm heart makes you ripe for exploitation. Your judgement will be so clouded by empathy that it’s inevitable you’ll be abused and taken advantage of. A compassionate person, from this perspective, is one who is a pushover. A milquetoast. Or as the woman on Facebook said with such depressing finality, a doormat.

But all the Tibetan lamas I have ever met come across as the very opposite. They are feisty and bold! You don’t have to look too far beneath their usually serene exterior to discover powerful resolve, grit and determination. They are most definitely not to be messed with.

How do we come to terms with this apparent contradiction? Given that compassion is central to the Tibetan Buddhist path, why is it that the products of Tibetan monasteries are such tough-minded individuals? Might it be possible to practice compassion without being walked over? I am sure that many of you, like me, aspire to live to our highest purpose, but we’re not so naïve as to believe that everyone else is: should we show compassion even when we suspect we’re being played?

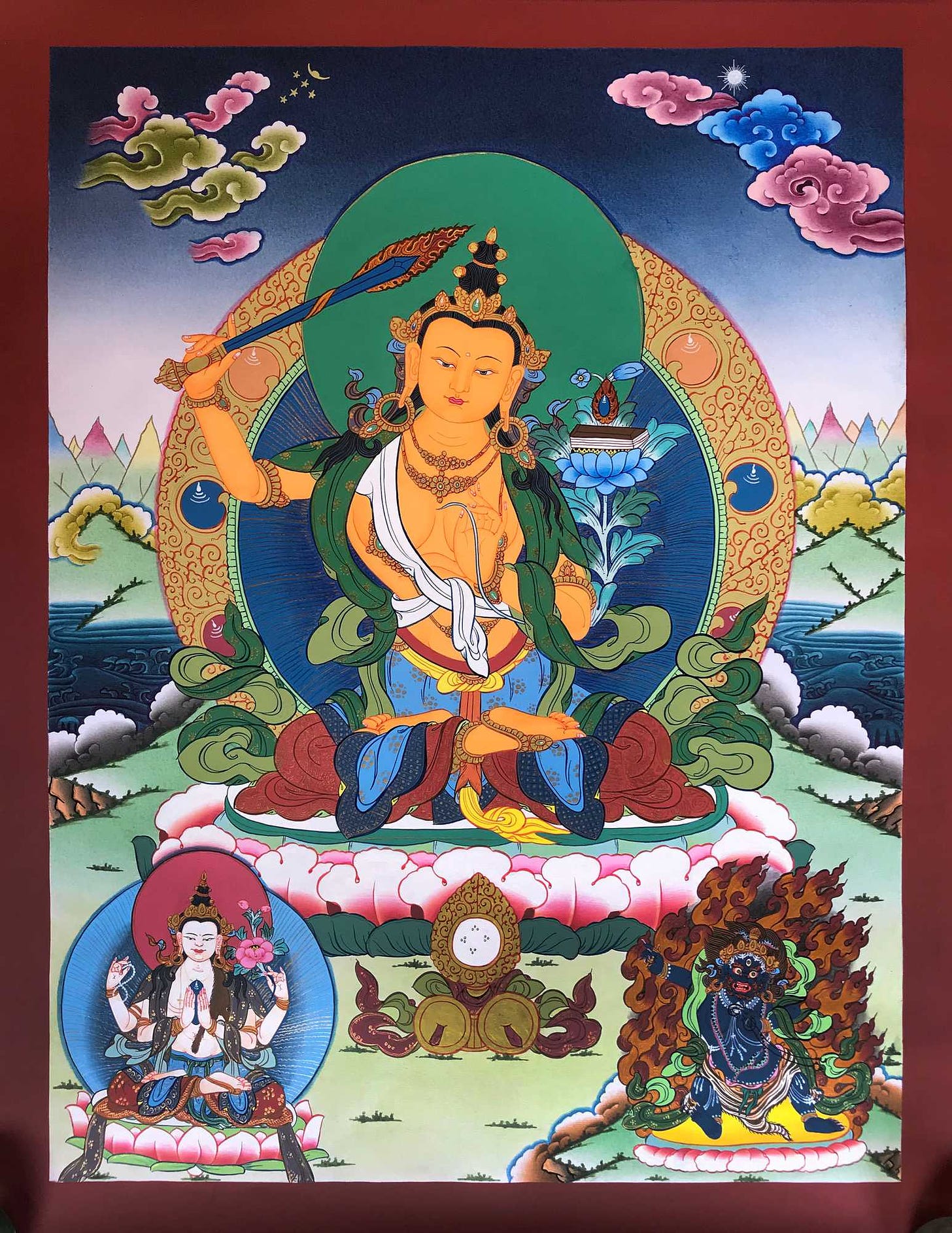

Tibetan Buddhism provides some very useful direction on this subject. Visually it is depicted in the illustration above, which is to be found on thangkas, or wall-hangings, in many temples.

The image shows three Buddhas who are widely recognised as embodiments of specific qualities. In the centre is the orange-coloured Manjushri, Buddha of Wisdom. To his right, the white-coloured Chenrezig, Buddha of Compassion, and to his left, Vajrapani, Buddha of Power. What these Buddhas, often presented in this particular combination, illuminate is that for compassion to be effective, it must be combined with wisdom and power.

Compassion without wisdom

Compassion does not mean giving way, handing over whatever people want, or being a martyr. It doesn’t meant we should allow ourselves to be emotionally manipulated by family members, friends, or anyone else. As Prof. Singer expresses so forcefully in his book The Life You Can Save (reviewed here), with so many individuals and organisations chasing our time and money, we need to apply rigour to the way we help.

If we wish to free someone begging on the street from suffering, does it help to hand him or her cash? I am aware that readers of these articles live in many different cities of the world. In some cases, a cash donation may go a long way to help. In others, it could support a cycle of addiction and deprivation. We need to exercise discretion.

It may sometimes help to ask why we are giving of our time, money or expertise. To cheer ourselves up? To look good in the eyes of others? To assuage our guilt? Because someone will try to make us feel bad if we don't? While our actions may have mixed motivations, none of these reasons is really about compassion.

My teacher tells the story of how a hard-working young couple he knew back in the early 1970s, converted to hippy-ish beliefs, sold their house and all their belongings and bought a campervan (recreational vehicle) to live in. They gave away all their money, confident that the universe would return their generosity in spadeloads. It didn’t. Years later, they regretted their impulsive actions, however noble - if ideologically unsound - they had seemed at the time.

Compassion without power

Compassion with wisdom, but no power, is simply pie in the sky – we don’t have the resources to do what we wish. I have long had a vision that instead of annual Mindful Safari visits to Africa, there could be a wildlife rescue conservancy permanently open to visitors. I and others who work in this space know how profoundly healing and transformative nature-based experiences can be, and that a dedicated reserve would benefit not only the animals and visitors, but local and broader communities. But I put that idea asside: it is too vast in scale and would cost millions that I just don’t have right now. Instead, I am focusing on what I am able to do – like fundraising for animal rescue centres and Buddhist charities via this newsletter. I feel it is better to do something modest than just sit here dreaming.

We need to be considered in how we spend our time helping others. Time is the only resource, the only power, that is finite. Whatever we spend our time doing is, by definition, not being spent doing something else that could also be beneficial. Being aware of such trade-offs as well as and the consequences of our actions, are all part of the wisdom that accompanies our practice of compassion.

Summary

Compassion, on its own, is not enough. Being compassionate certainly doesn’t equal tolerating rudeness, yielding to others’ expectations, or allowing ourselves to be manipulated.

By exercising wisdom along with compassion, and by having the power to ensure that our actions bear fruit, we are best able to fulfil our purpose of helping free others from suffering.

About half the money readers help me raise through subscriptions goes to the following four charities. Feel free to click on the underlined links to read more about them:

Wild is Life - home to endangered wildlife and the Zimbabwe Elephant Nursery; Twala Trust Animal Sanctuary - supporting indigenous animals as well as pets in extremely disadvantaged communities; Dongyu Gyatsal Ling Nunnery - supporting Buddhist nuns from the Himalaya regions; Gaden Relief - supporting Buddhist communities in Mongolia, Tibet, Nepal and India.

A few pictures in this week from Twala Trust Animal Sanctuary, which you support through your subscription:

The view from the feed station on a busy, busy Doggy Tuesday - we are committed to lifelong care for the hundreds of rural dogs registered with the programme.

Dr Godfrey Chifaka is always unfazed by the varied assessment of patients coming in to the 24 Hour Vet from Twala. All surgical procedures and treatment of sick and injured animals from Twala is done free of charge and without this extraordinary support our work at Twala would not be possible.

A nursery full of wild babies, loved, safe and on a journey back to freedom.

You may be interested in a related post about the difference between empathy and compassion:

Thank you David for this reminder.I could write for days on this subject.

I remember a time when it seemed the homeless population where I lived was growing larger every week and many were on corners with dogs by their sides. For me personally to cross paths with people with pups asking for help was a no brainer having having dedicated my life to animal compassion so to help with dog food, water and lunch I carried supplies with me just in case and got to know many men and their dogs by name over many months.,

One man in particular had 3 dogs tied together by rope and asked me if I could buy him collars and leashes…Because I could, I did , but that was my choice and on that day I realized it was my destiny to help possibly more than homelessness was his!

For me it was an act of love that He asked me and that small exchange sent my heart soaring . I felt from that point on ,anytime I could help a homeless person even in the smallest of ways was a gift from God….and it was no mistake that our paths crossed….sometimes a situation or person we don’t know is a teacher who allows us to grow in LOVE and open our hearts even more than we thought possible. That’s power🌹That’s compassion 🌹.And a beautiful gift! 🌹

I think we often forget that our first act of compassion should be to ourself.