Years ago I was in one of those undercover markets, where you never know what kind of stall is round the next corner. I came across a beautiful statue of the Buddha. As I stood admiring it, the stallholder told me, “Of course, Buddha never wanted images of himself to be made.’

‘Didn’t he?’ It wasn’t a subject I’d ever thought about.

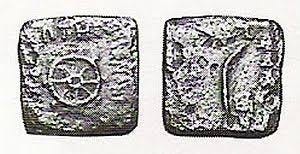

‘In the early days after he died, they just used symbols to represent him, like the eight-spoked wheel.’

It was the first time I’d heard this. But the words had a ring of truth about them. Central to Buddha’s teachings is the idea that nothing out there, not even Buddha himself, exists with its own characteristics, separate from our mind. I could see why the idea of statues, setting certain ideas about him quite literally in stone, would not be consistent with this particular message.

Later, I discovered that in the Vedic traditions from which Buddhism arose, the highest beings were seen as ultimately transcended and formless. They were not to be reduced to the material realm of mere mortals.

So why were statues of the Buddha front and centre of every temple I’d ever visited? How come some groups went to extraordinary efforts to build the largest Buddha sculptures in their countries, or to fill the walls of their temples with more Buddha statuettes than could be counted? Where was all of that coming from?

It was years before I stumbled across the explanation – which was different from anything I would have imagined.

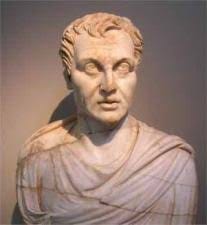

Back in 200 BCE, about three hundred years after the time of Buddha (563 – 483 BCE), King Demetrius I invaded the Indian Subcontinent, and established an Indo-Greek kingdom. The arrival of Greek influence in a part of the world where Buddhism was thriving, would turn out to be pivotal for both West and East. Indo-Greek kings supported Buddha’s teachings, with the most famous among them, King Menander, becoming a practising Buddhist himself (photo of a sculpture of him above).

Menander was a great patron of Buddhism. He supported the writing of Buddhist texts, now the oldest Buddhist manuscripts known, a few of them currently housed in the British Library. Some of his coins bore the eight-spoked Dharma Wheel (symbolising the Noble Eightfold Path). When he died, his remains were interred in a number of stupas throughout his kingdom, in keeping with Buddhist tradition.

It’s fascinating to me that Buddhism wasn’t simply known about in “the West”, more than two millennia ago. It was being studied, practiced and championed by the most influential leaders of the time.

Gandhara, part of the Indo-Greek empire, and the epi-centre of Buddhism, was to remain a huge influence until 1200 CE because of its location at the very centre of the Silk Route, between the far edges of Egypt and Turkey to the West, and China to the East. There is nothing more transportable than an idea, and Buddha’s ideas were transmitted throughout the world, influencing Greek philosophers and Western thought more broadly, long before most of us usually imagine.

Where it gets really interesting is that this process of influence wasn't a one way street. The West influenced Buddhism in the most profound way too. It was only in the first century BCE that the first statues of Buddha appeared - in the Greco-Buddhism kingdom. Not bound by Vedic restrictions, and instead, driven by the Greek love of form, early sculptors sought to create images of Buddha in classical Greek style. Guided by notions of idealistic realism which prevailed at the time, they strove for realistic anatomy, ornate details and expressive movement. Sculptors gave Buddha the full, classical treatment, including stylized Mediterranean curly hair and topknot.

These early statues were the prototypes of all the Buddha statues we see today. So successful were those ancient Greek sculptors at conveying a sense of serenity, they began a tradition which continues to this day.

It was only well after the first Buddha statues appeared that Buddhism was adopted in other parts of the world, including Tibet – and along with it, statues of Shakyamuni Buddha himself, which took on more Asiatic features the further East they travelled.

In his Foreword to Echoes of Alexander the Great: Silk Route Portraits from Gandhara, His Holiness, the Dalai Lama writes: “One of the distinguishing features of the Gandharan school of art that emerged in the north-west of India is that it has been clearly influenced by the naturalism of the classical Greek style. Thus, while these images still convey the inner peace that results from putting Buddha’s doctrine into practice, they also give us an impression of people who walked and talked, etc. and slept much as we do. I feel this is very important. These figures are inspiring because they not only depict the goal, but also the sense that people like us can achieve it if we try.”

The interactions between Greek and Buddhist thinking is also fascinating - and the subject of an article by the writer, scholar and philanthropist, Dean Kalimniou: http://diatribe-column.blogspot.com/2008/03/greek-buddha-where-east-meets-west.html

Without the inspiration of Shakyamuni Buddha, there would have been nothing for those early sculptors to portray. But there's no doubt either that they were either Greek or influenced by classical Greek style. There's something quite wonderful about how we conceive of Buddha, and continue to reproduce his image today, being the joint creation of both East and West.

I hope you found this blog interesting. If you did, subscribe to me on Substack to get regular articles, guided meditations, book recommendations and other stimulating and useful stuff!

Here are a few other things you can also do if you choose:

Check out my books which explore the themes of my blogs in more detail. You can read the first chapters of all my books and find links to where to buy them here.

Have a look at the Free Stuff section of my website. Here you will find lots of downloads including guided meditations, plus audio files of yours truly reading the first chapter of several of my books.

Join me on Mindful Safari in Zimbabwe, where I was born and grew up. On Mindful Safari we combine game drives and magical encounters with lion, elephant, giraffe, and other iconic wildlife, with inner journeys exploring the nature of our own mind. Find out more by clicking here.

Very interesting. I think the Buddha statues are good for modeling serenity, peace, & tranquility. Just looking at a statue is a meditation in itself.