Before we begin this week’s post, thank you so much to my paying subscribers for such enthusiastic and engaged responses to my article last week about my Dad. I was amazed how many of my own experiences resonated with you, and how different elements chimed with different people.

With so many readers reflecting and sharing about their own formative years, there was a real sense of drawing together, summarised beautifully by Susan Neilson who commented: “I truly feel a part of a much larger group of like-minded people throughout the world. And, I love it! Wouldn’t it be phenomenal if we could ALL be together just one time with you!”

Wouldn’t it just? I love the feeling too! And I especially love that we’re not just a talking shop of idealistic do-gooders, but that despite being scattered around the world, because of our shared values we’re collectively delivering life-changing help to extremely vulnerable animals and people. In some cases, life-saving help.

So let’s hold virtual hands for a moment, take a deep breath in, and as we exhale, do so with a sense of gratitude, connection and the heartfelt recognition that we are doing something truly worthwhile.

An appropriate state of mind to begin today’s post …

Impermanence is one of our most powerful contemplations. No matter what our beliefs, or lack thereof, a focus on impermanence can awaken a powerful sense of gratitude. It can help set and energise our priorities like few other contemplations. And, if we happen to believe that some aspect of consciousness continues after death, contemplating our own impermanence can help us prepare what is arguably the greatest opportunity of our lives.

Gratitude

We value what is scarce. Rarity is what makes diamonds more expensive than emeralds and rubies, and hundreds of times more valuable than zirconia. When we have an apparently endless supply of anything, it isn’t precious to us.

Many of us go through much of our lives with the assumption that an eternity of tomorrows stretch ahead. It can sometimes feel like there’s a permanence to our reality bordering on the insufferable. How often do we hear people say, on a Monday, “I wish it was Friday.” Or “I can’t wait until we go away in June.” We’ve all had the sensation, maybe even often, that time is something to be endured as we limp our way through ‘groundhog’ weeks or months to a particular date when some wonderful excitement is planned.

If our reality already seems tedious, it may seem like an act of masochism deliberately to remind ourselves that it is also tenuous. That we may not make it to June. Or, for that matter, Friday. Plenty of people aren’t going to. People just like us who have no idea they are about to be involved in a fatal accident, receive a dread diagnosis, or whose world is going to be otherwise turned upside down. But when we consider exactly this, not as a passing abstraction but as a real possibility, it helps us from overlooking the myriad tiny miracles that, in themselves, are more than enough to make life worthwhile.

In his book The Nostalgia Factory, memory specialist Douwe Draaisma describes why Christmas takes so long to come around each year for children while, for adults, it seems like we’ve barely put away the Christmas baubles and the next festive season is about to happen. Draaisma explains that when there is a novelty to things, the vivid and engaging quality of the experiences has the effect of slowing down our subjective experience of time. By contrast, time races when we’re on autopilot.

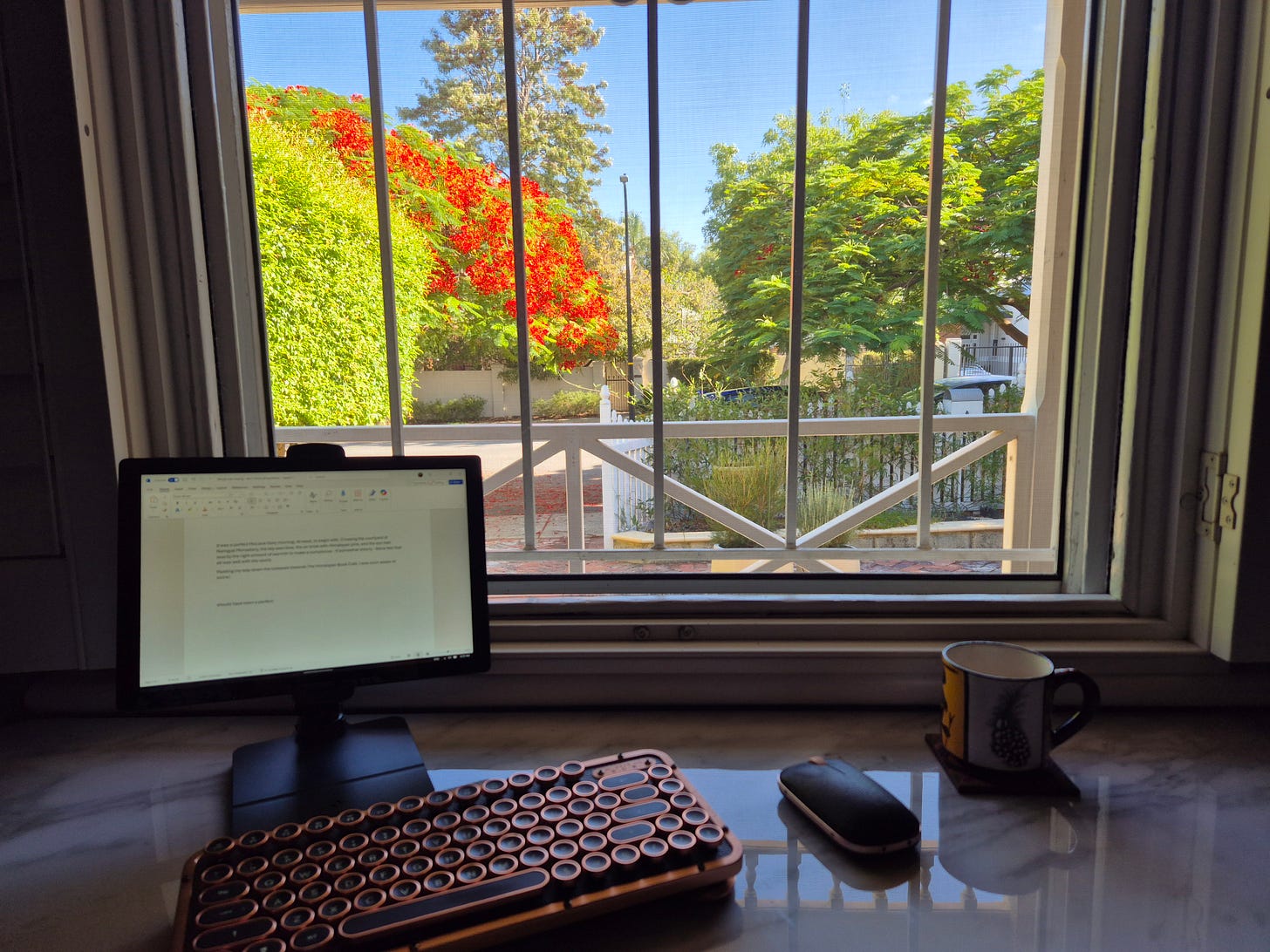

Remembering impermanence helps take us off autopilot. Instead of wishing away precious time until some milestone event, it encourages us to more forensically experience that taste of coffee, or enjoy that movement of tree branches in the wind. Even take momentary pleasure in something as simple as being able to stand, raise up our arms and drink in great, relaxed breaths of clean air.

Photo: the view from my writing desk on a typical summer morning. The taste of coffee and movement of flamboyant tree branches in the wind …

These aren’t things that will always be available to us. There will come a time when we take our last walk by the sea. When an exhalation won’t automatically be followed by an inhalation. At a recent Dharma class, my teacher observed how there will come a day when we have stepped into the last year of our life - and there’s every chance that we won’t know it.

As we grow older, our sense of impermanence perhaps becomes more real. How many funerals do we have to attend, how often do we need to hear about the death of contemporaries or their families, to recognise that one day, I, too, will be the one about whom people say: “Did you hear that David Michie died?”

The reality of our own death is still usually a prospect we want to place comfortably over the horizon - even when we should know better. I went to visit a Buddhist friend, Yvette, who was dying of cancer. She’d been through treatment, years earlier and went into remission for a long period before the cancer returned. Yvette was shaken by the first diagnosis, she said, but it hadn’t taken her long, after she seemed to have beaten the disease, before she was back taking life for granted, counting down the months impatiently until a visit to Europe to see family and friends.

The morning of our last conversation Yvette was sitting in the sun overlooking a garden. She’d never seemed so happy or at peace. On her lap was The Path to Enlightenment by our lama, Geshe Thubten Loden which she had got into the habit of reading, cover to cover, every week. Talking to her, I had the sense that at that moment, everything for her was perfect. It was quite extraordinary. Yvette hadn’t always been a comfortable person to be around. She certainly hadn’t had an easy life. Right now, she had a terminal diagnosis and was days off death. But it was self-evident from her expression, and what she said, that for her there was something miraculous about simply sitting in the sun in the garden. It was all she needed. All any of us need - if only we had the capacity to recognise the extraordinary preciousness of life itself.

How much happier would be all be if we could fully grasp this fact in the midst of life, instead of waiting until death is imminent? What does it take for the reality of it to sink in? What should we do for our understanding to go deeper than intellectual, for it to affect our response to even mundane reality, as it so radiantly affected Yvette’s?

As an interesting conclusion to that story, a friend who came to offer care was in Yvette’s room a few evenings later. The friend, who was the opposite of excitable, turned to Yvette and observed, uncharacteristically “There are a lot of Buddhas in the room this evening,” to which Yvette, equally phelgmatic, replied, “Yes, I know.”

She died in the early hours the following morning.

I would like to tell you that I saw rainbows streaming from the windows of her room. That showers of rain fell from a cloudless sky and the sound of distant conches could be heard echoing through the heavens. None of that happened. But I had already witnessed a more relatable miracle: the abundant wellspring of gratitude that arises from the realisation of impermanence.

Priorities

Along with heartfelt gratitude, living with a keen awareness of life’s evanescence helps us prioritize. Imagine, for a moment, that you are arriving at a magnificent hotel for a vacation. You choose the destination, dear reader. As you approach the Concierge desk, you are greeted by name and told that you’ve been given a free upgrade to their very best suite. You are shown to the lavish accommodation that is all yours, and pointed to a list of the amazing services that, as a VIP visitor, are also free for you to enjoy.

Is this an experience that causes you to burst into tears of misery? Do you immediately think, “It’s going to be the most terrible ordeal having to drag myself away from here in seven days’ time?” Or are you more likely, after an initial bout of euphoria, to wonder “What, exactly, is going on in the next week, and how can I make the most of it?”

This very thing happened to my wife and me, so it’s not a hypothetical. It was on a Mediterranean cruise ship, rather than a hotel, and I am guessing that there was an Aussie in their reservations team bestowing largesse. Initially, we weren’t even convinced the lavish suite was ours - was there some kind of mistake? - until we saw our names on the welcome TV screen of the sitting room. I can assure you that there was no wailing or gnashing of teeth going on in the Wintergarden Suite! Only the wish to take part in as many of the wonders available.

The hotel suite or cruise ship cabin is our life. And as human beings with leisure and fortune, we are definitely at the upscale end – no matter how it may sometimes seem. How much agency do most sentient beings have compared to us?

So here we are, with all these prospects. The downside is that we only have them for a very limited time. The main question, surely, is how best to make the most of an extraordinary but finite opportunity?

Our human herd instinct is that we’re immune to time. We may embark on jobs and relationships and otherwise invest our energy based on an illusion of permanence that’s entirely false. One of my kind Dharma teachers, called to the beds of the dying, says that the thing he hears most often is: “Was that it?” People feel somehow that there will be more time, more opportunity, more life to live than they actually had.

In her book, The Top 5 Regrets of the Dying, nurse Bronnie Ware, who worked in palliative care, writes about the insights very commonly experienced by terminally ill people. She summarises these as follows:

• I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life that others expected of me;

• I wish I hadn’t worked so hard;

• I wish I’d had the courage to express my feelings;

• I wish I had stayed in touch with my friends;

• I wish I had allowed myself to be happier.

‘Start with the end in mind,’ is a well-known aphorism relevant here. When our own end comes, when it’s our turn to lie on our deathbed, how would we like to feel about the measure of our days? If death comes soon, are we likely to have such feelings? Is there anything we need change to better align current reality with our ideal end point? This is a second way in which impermanence can be a powerful contemplation.

Preparing for death

The Buddhist definition of mind is ‘clear knowing.’ ‘Clear’ means formless. ‘Knowing’ means that mind cognises what is presented to it. This continuum of clear knowing is energetic and as such cannot be destroyed, even though it constantly changes.

For those who lean towards the Buddhist presentation of death, it suggests an opportunity like none other. How about, instead of incarnating in physical form through the force of habitual self-grasping, we do something different? What possibilities for consciousness might exist apart from the varieties we know all too well? And just like that vacation, might we have a more fulfilling, useful, delightful experience if we do some pre-trip preparation? No sane person would show up at the airport to travel to a place they’d never visited without finding out at least something about their destination, or making some plans for once they get there. Why the complacency about our greatest existential leap?

You can read my previous post about the death process here. Although written in the context of a booklet for pet lovers, it sets out the main stages and basis for our understanding of them.

Contemplating our own impermanence offers a focus to practices like meditation. When we understand their transformational benefits not only in life, but at the time of death also, our inner journey is invigorated by both urgency and purpose.

Summary

When our hearts and minds are steeped in the wisdom of impermanence, we live in gratitude for the constant flow of exquisite moments it is our privilege to enjoy even on the most ordinary of days. Our endeavours reflect who we are and what truly enlivens us. And our practice becomes a force of transcendence, enabling states of awareness beyond our usual conditioning, where we may find our greatest flourishing - both for our own sakes, as well as for others.

“Of all footprints, the elephant’s is supreme.

Of all perceptions, remembering death and impermanence is supreme.”

Buddha, Great Nirvana Sutra

Talking of elephants, I wanted to share some gorgeous elie pics from Wild is Life/Zimbabwe Elephant Nursery, one of the three causes you support as paying subscribers to this newsletter. They were published to celebrate Valentines Day, with the message that “Love comes in all shapes and sizes – sometimes with tiny trunks and giant hearts.”

These very young orphans are given all the love and care they need so overcome the trauma of separation, before being introduced to fellow orphans.

One day, when they are very big, they will have the chance to meet Matriarch Moyo (below with Roxy) at the Panda Masuie release site where, if they choose, they can roam free, become part of wild elephant herds and have their own calves.

May all beings have happiness and its causes!

Please feel free to share this post on impermanence with anyone who you feel may benefit from it:

To become a free or paying subscriber, click the button below:

Thank you David for reinforcing what we often forget. I have the extraordinarily good fortune to live on land in the country. We have lived here for 30 years. It takes alot of work and I haven't always appreciated it but over the last few years, since reading your books and as the realization grows that our time here is short I have found myself more often stopping to take in the beauty and just be grateful for the moment. Gratitude helps to engender a sense of peace about whatever is to come, whenever that might be.

Heartfelt thanks,David,for this timely reminder of our impermanence